This was one of the first interesting memorials that we came across. Neither of us was familiar with the name, but the figure clearly seemed to be an explorer of some sought. There were also several grave markers in front of the statue, all apparently deceased on the same date. We guessed that these were members of an expedition that went horribly wrong and when I looked up the name afterwards I discovered that we were correct.

According to Wikipedia:

Born in New York City, he was educated at the United States Naval Academy, and graduated in 1865. In 1879, backed by James Gordon Bennett, Jr., owner of the New York Herald newspaper, and under the auspices of the US Navy, Lieutenant Commander De Long sailed from San Francisco, California on the ship USS Jeannette with a plan to find a quick way to the North Pole via the Bering Strait.

As well as collecting scientific data and animal specimens, De Long discovered and claimed three islands (De Long Islands) for the United States in the summer of 1881.

The ship became trapped in the ice pack in the Chukchi Sea northeast of Wrangel Island in September 1879. It drifted in the ice pack in a northwesterly direction until it was crushed in the shifting ice and sank on June 12, 1881 in the East Siberian Sea. De Long and his crew then traversed the ice pack to try to reach Siberia pulling three small boats. After reaching open water on September 11 they became separated and one boat, commanded by Executive Officer Charles W. Chipp, was lost; no trace of it was ever found. De Long’s own boat reached land, but only two men sent ahead for aid survived. The third boat, under the command of Chief Engineer George W. Melville, reached the Lena delta and its crew were rescued.

De Long died of starvation near Matvay Hut, Yakutia, Siberia. Melville returned a few months later and found the bodies of De Long and his boat crew. Overall, the doomed voyage took the lives of twenty expedition members, as well as additional men lost during the search operations.

National Geographic also has an interesting article on the Jennette story (see The Hair-Raising Tale of the U.S.S. Jeannette’s Ill-Fated 1879 Polar Voyage in the form of an interview with Hampton Sides author of The Kingdom of Ice: The Grand and Terrible Voyage of the U.S.S. Jeannette.

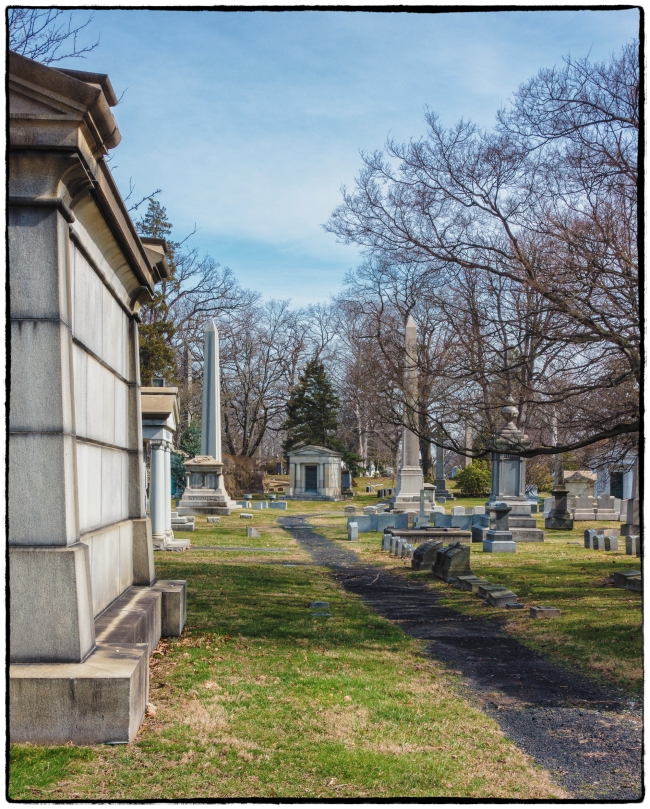

Closeup of the memorial.