According to The Guggenheim:

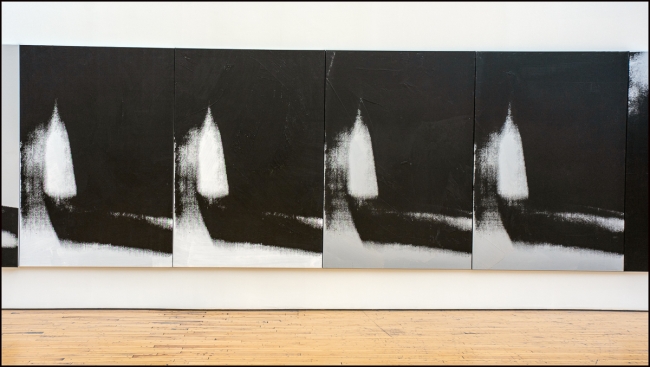

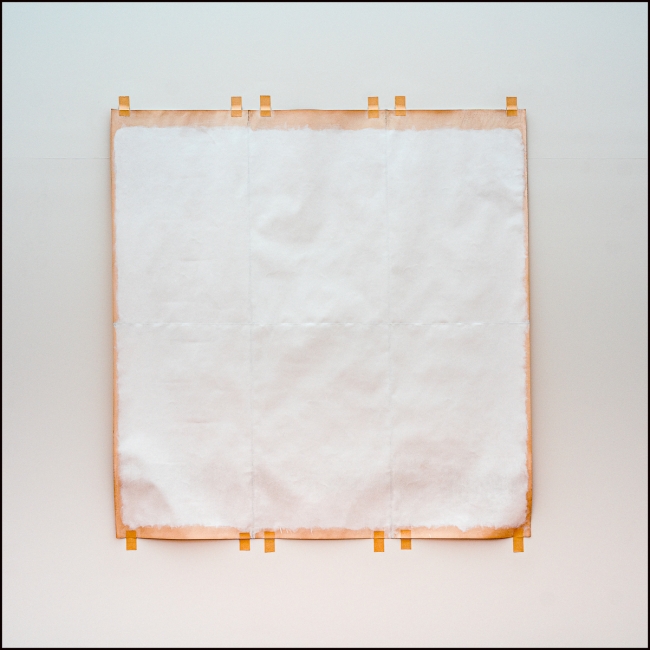

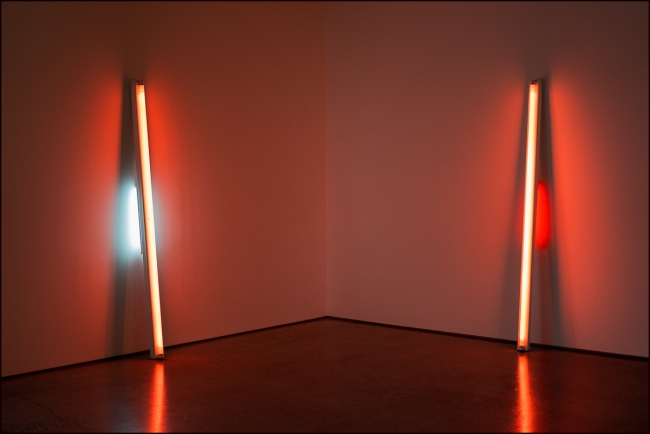

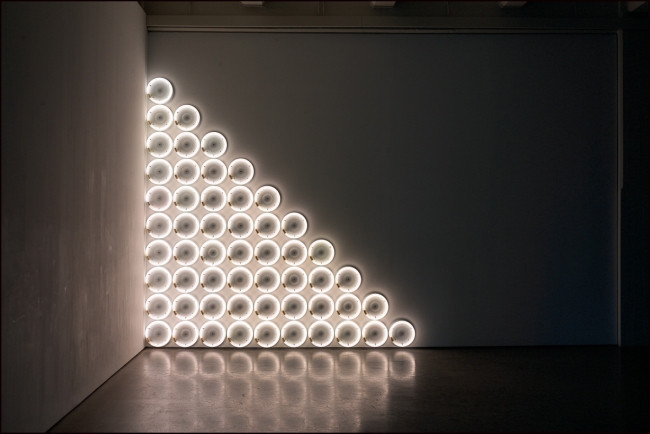

Larry Bell was born in Chicago in 1939 and grew up Southern California. Bell attended the Chouinard Art Institute in Los Angeles from 1957 to 1959, where he created abstract oil paintings dominated by gestural brushstrokes influenced by Abstract Expressionism. At Chouinard he met Robert Irwin, an influential arbiter of Perceptualism, who profoundly affected how Bell conceptualized vision. From 1960 to 1962, Bell created a series of shaped canvases with the corners lopped off, onto which he painted simple polygonal forms that mimed the form of the canvas. By 1962 Bell had integrated both mirrored and transparent glass into his painting in several collage constructions; the different types of reflective glass created spatial complexity, conflating the world of the viewer with that of the object. Bell soon transitioned to sculpture with shallow boxes of glass onto which he painted geometric shapes. In 1963, Bell developed his signature glass cubes, the earliest versions of which were covered with opaque designs of stripes, checkers and, most commonly, ellipses. Several of the ellipse-covered cubes were included in Bell’s solo exhibition at the Pace Gallery in New York in 1965, which sold out on its first day. Bell moved to New York soon after this successful exhibition, but stayed for only a year before returning to Southern California. The artist abandoned the geometric surface designs and created his famous elegant vacuum coated glass cubes with chrome frames from 1964 to 1968. In these new works, often included in major exhibitions on Minimalism, Bell explored the properties of glass by offering subtle gradations of transparency, reflectivity, and color. These faint variations, achieved by specialized machinery Bell obtained for his studio, supply seemingly simple forms with complex inquiries into the nature of perception. In 1968 Bell began to abandon the chrome frame and create larger cubes in which the effects of the planes of glass interact only with one another. This development led to Bell’s glass panels, which stood eight feet tall, operated at an almost architectural scale, and could be arranged in countless configurations in the gallery space. In 1973 Bell moved to Taos, New Mexico, where he established a studio and created the huge fifty-six-panel adjustable glass structure The Iceberg and It’s Shadow (1974). In the late 1970s Bell initiated his Vapor Drawings and Mirage Paintings, which extended the artist’s investigations into perception, but this time on a flat plane. Since the late 1970s, Bell has engaged with such diverse practices as furniture design and bronze sculptures, as well as large-scale glass sculptures and installations like Moving Ways (1981–82), The Wind Wedge (1982), and Made for Arlosen (1992).

Solo exhibitions of Bell’s work have been organized by the Pasadena Art Museum (1972), Oakland Museum of Art (1973), Fort Worth Art Museum (1975 and 1977), Washington University in St. Louis (1976), Detroit Institute of Arts (1982), Museum of Contemporary Art in Los Angeles (1986), Denver Museum of Art (1995), and Alberquerque Museum (1997). His work was also included in major group exhibitions such as The Responsive Eye at the Museum of Modern Art in New York (1965), Primary Structures at the Jewish Museum in New York (1966), Guggenheim International (1967), Documenta 4 (1968), and Venice Biennale (1976). In 1970 Bell received a Guggenheim Fellowship. The artist lives and works in Taos, New Mexico, and Venice, California.

For more information see here on the Dia Beacon website.

Taken with a Sony A7IV and Samyang 45mm f1.8