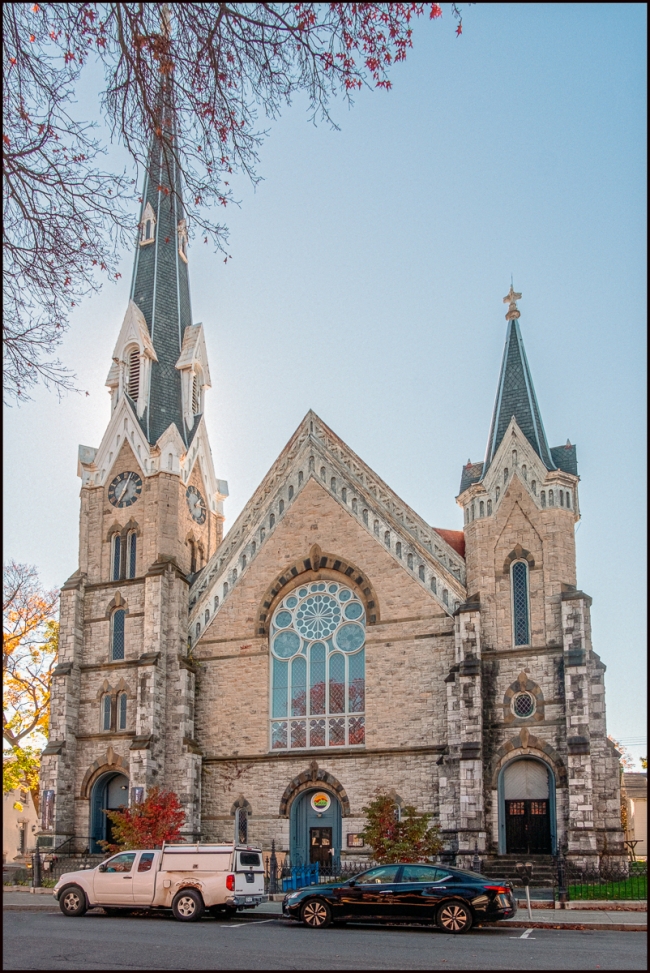

After lunch we were due to leave for Olana, but I managed to grab a few minutes for a very short walk along Warren Street in the Historic District.

“The Hudson Historic District includes most of downtown Hudson, New York, United States, once called “one of the richest dictionaries of architectural history in New York State”. It is a 139-acre (56 ha) area stretching from the city’s waterfront on the east bank of the Hudson River to almost its eastern boundary, with a core area of 45 blocks. It has 756 contributing properties, most of which date from the city’s founding in 1785 to the mid-1930s. In 1985 it was listed on the National Register of Historic Places.

It includes part of Hudson’s original Front Street-Parade Hill-Lower Warren Street Historic District, excluding portions which were demolished soon after that district was designated in 1970. It is one of the rare downtowns to have followed the grid plan laid out by its 18th-century founders through the present day, and Warren Street, its main artery, is New York’s most intact 19th-century main commercial street.

The oldest buildings in the district reflect the city’s post-Revolutionary origins as a safe harbor for New England whalers, a past alluded to today by the whales on the street signs. It later became an industrial center, with areas of worker housing and grand homes of factory owners in its downtown. In the early 20th century, the rise of officially-tolerated prostitution on what is today Columbia Street made the city known as “the little town with the big red-light district.”

Historic preservation efforts since the district’s establishment have helped spur the city’s economic renewal. Shortly after the district was designated, antiques dealers began setting up shops on Warren Street, leading eventually to what The New York Times described as “the best antiques shopping in the Northeast”. Art galleries followed, and many weekend visitors have relocated to Hudson full-time, including some celebrities. The new arrivals have restored old houses they have purchased. The city has established a Historic Preservation Commission to protect the district’s historic character.” (Wikipedia)

Above: The Cornelius H. Evans House.

“Listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1974 and located approximately two blocks from the Front Street Parade Hill-Lower Warren Street Historic District, the Cornelius H. Evans House fronts upon the main street in the city’s commercial downtown. Constructed of brick with sandstone trim, the Evans House is composed of a 2 1/2 story mansard-roofed rectangular block with a three-story tower which terminates in a pyramidal roof. The scheme of the five-bay front (south) elevation is axial, focused upon the central bay which contains the substantially enframed main entrance connected above to a classical feature surrounding the central second-story window and a tripartite dormer window. Windows are rectangular except for the round-arched and circular windows of the tower. The originally open veranda found in the re-entrant angle on the west elevation was enclosed by means of glass panes ca. 1920 for use as a solarium.

The interior space, heated with the aid of interior end chimneys, is arranged according to an axial scheme around a central hall which contains the original staircase and panelled wainscoting. Scrolled archways define the spaces which flank the central hall, and a pronounced raised-pattern paper in imitation of tooled leather adorns the wall surfaces throughout the first floor. Although portions of the interior have been altered for use as a community center, there remain still heavily molded woodwork, original ornate white marble mantels, stained glass, china and brass hardware on the doors, and interior shutters. The sequence of spaces and the decorative trim in the tower remains essentially unaltered.

Significance

Architecturally and historically the Cornelius H. Evans House imparts to Hudson a significant aspect of the city’s identity. Built in 1861, the brick and sandstone dwelling represents the achievements of the Evans family, the entrepreneurs behind one of the city’s major 19th century industries. Situated in Hudson’s commercial downtown, the structure is a well-preserved asset to the visual character of the city.

A modest commercial center during the colonial period, the city of Hudson was founded in 1783 by a Proprietors Association “for the purpose of establishing a commercial settlement.” As the middle of the 19th century approached, the city was prospering as a hub of commerce, industry, navigation and transportation for the surrounding region. In 1836 businessman Robert Evans purchased a brewing company with branches in Hudson and New York City that had been established in 1796 by George Robinson. Under Evans’ direction, the enterprise quadrupled in business with the result that by the middle of the 19th century the Evans family was firmly entrenched in the economic life of the city. Educated at the local public school, the Hudson Academy and Bradbury’s Private School, Cornelius Evans (1841-1902) at 19 joined his father’s company as a clerk, rising to corporate member in 1865. Upon the death of his father in 1868, Cornelius purchased the entire family interest in the brewery and formed C. H. Evans & Company, dissolved ten years later when his partner retired and he assumed complete control. Under Cornelius Evans’ direction the brewery thrived to such an extent that in 1889 Evans opened a bottling works as an adjunct to the firm. The firm’s specialty during this period was “Evans India Pale Ale,” billed in a contemporary advertisement as a brew “than which no purer, more delicate, health-giving, and invigorating preparation from malt and hops can be found.” By 1890 the brewery’s response to demand for its products had necessitated doubling the capacity of the bottling works.

The business acumen of Robert and Cornelius Evans placed the family among the financial, social and political leadership of Hudson. A Trustee of the Hudson City Savings Institution, Cornelius succeeded his father as a director of the National Hudson City Bank, and was elected Mayor of the city, serving in 1872-1874 and again in 1876-1878.

The degree of the family’s entrenchment in the financial and social life of the city by mid-century is apparent in the house which Cornelius H. Evans built on the City’s main street. Built in 1861 when Cornelius was twenty years of age, the structure, attesting to the strength of Robert Evan’s financial enterprise by that date, appears to be a firm commitment on the part of Cornelius to the family’s economic and social stability which he augmented through an active career spanning the second half of the 19th century. A house of ample dimensions, with its mansard roof and pyramidal-roofed tower typifies a style fully articulated in America by James Renwick in his Corcoran Gallery, (Washington, D.C., 1859) and his Main Hall, Vassar College (Poughkeepsie, N.Y., 1860), and expressed on a smaller scale in domestic architecture by affluent entrepreneurs in small 19th century industrial cities such as Poughkeepsie and Hudson. The generous size, the attention to decorative trim, and the pretension in overall design reflect the ambitions and the accomplishments of entrepreneur Cornelius Evans whose brewing and bottling enterprise proved to be one of the city’s major industries.

At Evan’s death in 1902, the property passed to Cornelius, Jr. (1866-1941). The latter continued to operate the family business with his brother Robert (b.1865) who had assumed their father’s position in banking and built a brick dwelling next door. In 1920 prohibition forced the Evans Company to close. At his father’s death in 1941 Roland Evans sold the house to William Friss. Purchased five years later by the Congregation Anshe Emeth, the property was utilized as a community center until 1970 when it was occupied briefly as a private residence. Today the house stands unaltered in the city’s business district, flanked by rows of commercial structures whose facades have been largely modernized. A representative of mid-19th century Hudson, it furnishes the streetscape with an uncompromised landmark whose absence would significantly deplete the historic and visual environment of downtown Hudson.” (Living Places)

A view along Warren Street.

White Window on a Blue Wall.

Gourds in a shop window. I don’t remember what kind of shop it was.

Taken with a Fuji X-E3 and Fuji XC 16-50mm f3.5-5.6 OSS II