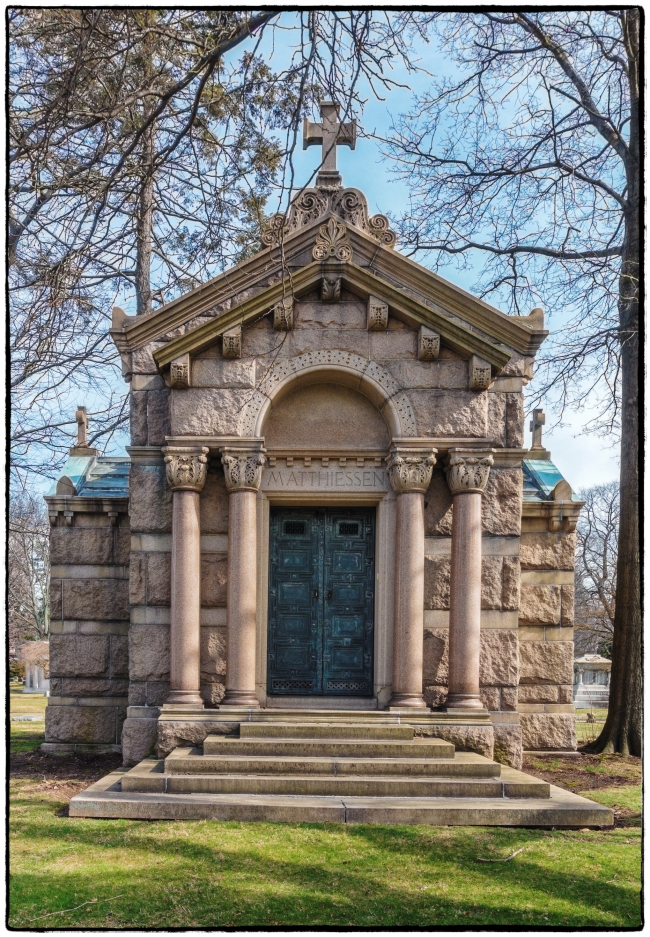

I just loved the way this one looked: the color of the stone; the diminishing size of the steps; the four columns, which do not seem to belong to any of the classical orders (maybe Egyptian?) and whose capitals are each carved differently; the bronze door; the cross above the open pediment with the ornate carvings beneath it. Lovely.

The National Register of Historic Places Registration Form (itself a fascinating, illustrated document covering a number of lesser known monuments about which information is not readily available elsewhere) for Woodlawn Cemetery contains this entry:

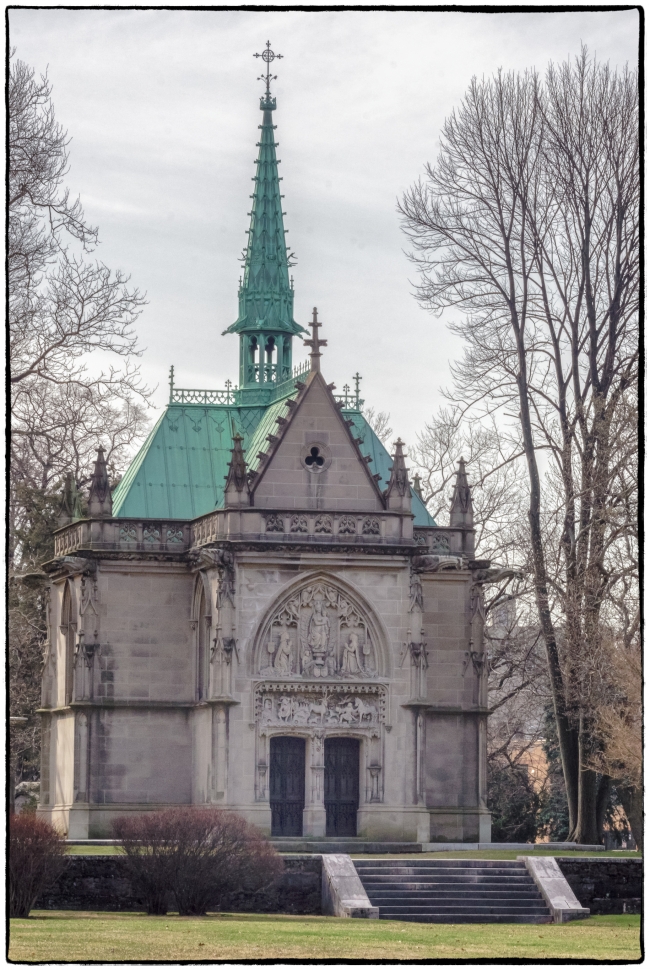

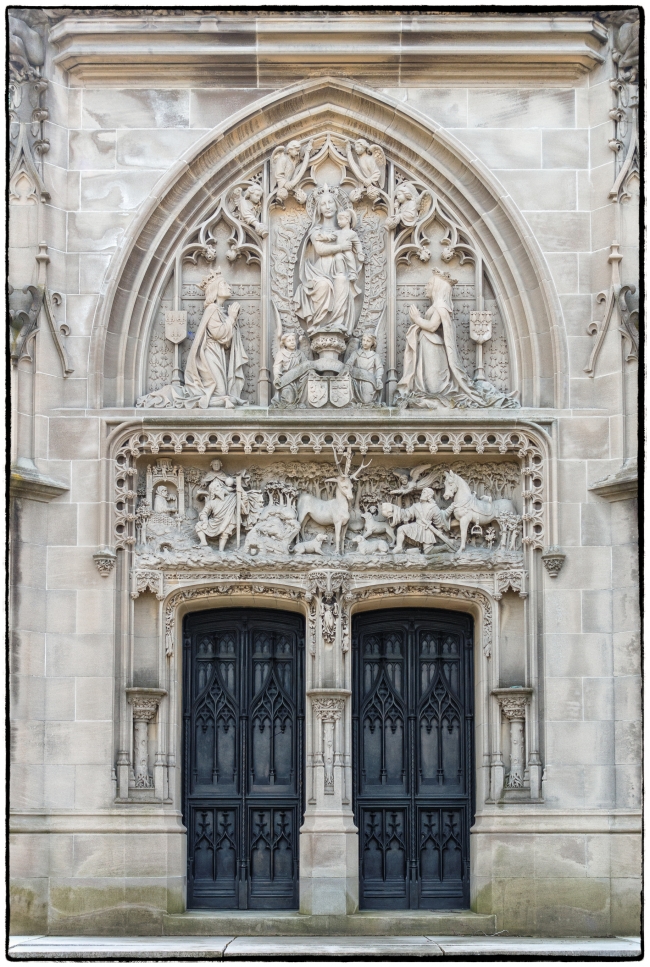

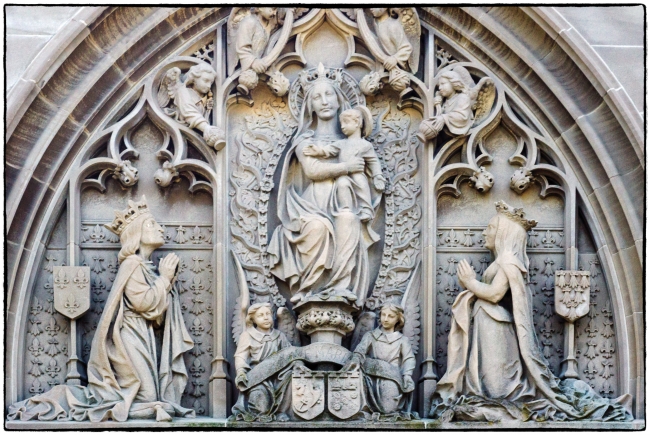

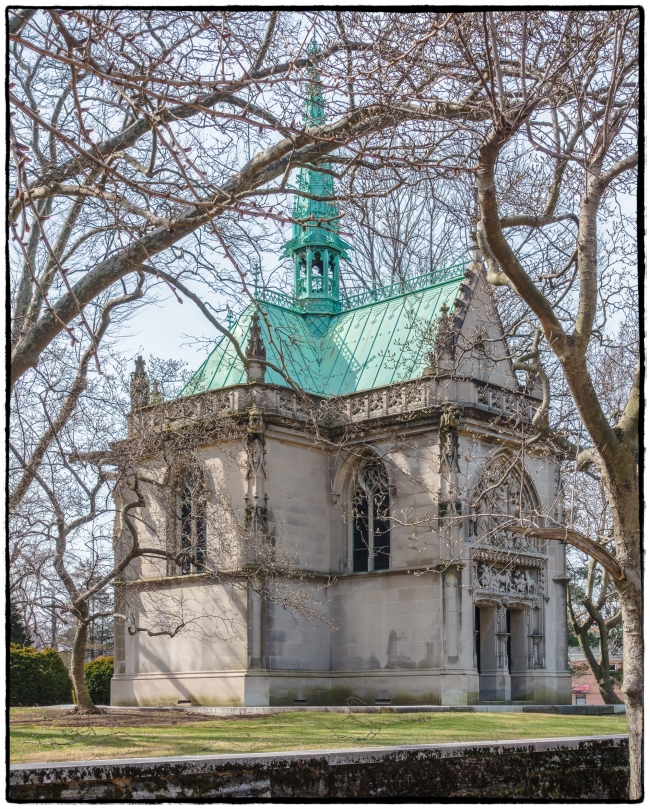

Franz O. Matthiessen mausoleum (structure) in Lake Plot, Section 61 has a series of windows by Tiffany Studios (1890). Designed by Heins and La Farge, the mausoleum is constructed of roughhewn red granite. Franz Mathiessen made his fortune in tobacco sales and distribution.

According to Wikipedia:

Heins & LaFarge was a New York-based architectural firm composed of the Philadelphia-born architect George Lewis Heins (1860–1907) and Christopher Grant LaFarge (1862–1938), the eldest son of the artist John La Farge. They were responsible for the original Romanesque-Byzantine east end and crossing of the Cathedral of St. John the Divine, New York, and for the original Astor Court buildings of the Bronx Zoo, which formed a complete ensemble reflecting the aesthetic of the City Beautiful movement. Heins & LaFarge provided the architecture and details for the Interborough Rapid Transit Company, the first subway system of New York.

As for Mr. Franz Otto Matthiessen. According to: Sugar House. American Sugar Refining Company. Sugar House Lofts at Liberty Cove, 174 Washington Street on New Jersey City Past and Present.

The largest of Jersey City’s sugar refineries was established by German immigrants Franz Otto Matthiessen (1833-1901) and William Alfred Weichers (1835-1888). Matthiessen had learned the basics of sugar refining as an apprentice in Hamburg, Germany. In 1858 he immigrated to America where he worked in several refineries in New York and Boston before opening his own establishment in Jersey City. He and Weichers founded the New Jersey Sugar Refining Company which soon became known as the Matthiessen & Weichers’ Sugar Refining Company.

Danish-born architect Detlef Lienau (1818-1887) designed the first refinery for the new company that was constructed in 1863 on the southern bank of the Morris Canal between Washington and Warren Streets. The firm was quick to implement technological innovations in sugar refining such as centrifugal processing. By 1875, Matthiessen & Weichers’ sugar refineries expanded north of the Morris Canal, and the company built a new seven-story office and warehouse on the site of the old Jersey Glass Works factory at the southwest corner of Washington and Essex Streets. The old American Pottery Company buildings on Warren Street between Essex and Morris Streets survived a little longer but these were finally demolished in 1892 for sugar house expansion.

Faced with recurring oversupplies of sugar and an overall decline in its price, owners of some of the larger refineries made various attempts to reduce competition within the sugar industry and revive profitability. By 1891, under the leadership of the Havemeyer family of Brooklyn, NY, several major sugar refining plants, including Jersey City’s own Matthiessen & Weichers Co., were consolidated under a single corporate ownership called the American Sugar Refining Company. The incorporation papers were filed in New Jersey to avoid New York State’s stricter regulations, which had earlier thwarted the Brooklyn-based Havemeyers. Matthiessen relinquished direct control of his Jersey City refineries, but maintained considerable influence as a Director and Treasurer of the new organization. Often referred to as the “Sugar Trust,” the industry remained a frequent target of anti-monopoly government lawsuits from its inception through the 1920’s.

An art collector and enthusiast, Matthiessen officially retired from the American Sugar Refining Company in January 1900 to pursue travel in Europe. However, he died not long afterwards and is buried in Woodlawn Cemetery in The Bronx, NY. At the time of his death, his estate was valued at approximately 15 million dollars.

His ‘Find a Grave‘ entry includes a scan (source not identified) of an obituary dated Paris, March 9, which contains the following poignant paragraphs:

Few men possessed a stronger physique than Mr. Matthiessen, and one of his closest friends said yesterday that he was sure Mr. Matthiessen’s death was precipitated by a broken heart. While in Italy in 1889, with her father nd mother, Mr. Matthiessen’s only daughter, Helen, then just twenty years old, died. She was a very beautiful woman, and was engaged to be married to an Italian Count.

The shock was a terrible one for the father and mother. Mr. Matthiessen brought the body home and kept it in his residence at Irvington-on-Hudson for several months, refusing to have it interred. He closed up his house at 580 Fifth Avenue and retired from all social life. He had been in deep mourning ever since. Mrs. Matthiesen was so stricken by the grief that her nervous system was undermined, and she is now an invalid.

Not surprisingly Helen Matthiessen is also interred in the mausoleum.