Art and creativity has always run strong in my family. My mother writes, my father creates stained glass, and my brother creates music. All through school I took the usual art classes, learning drawing, painting, and sculpture, all through elementary school and into high school. Sure I was okay at them, but there never was any passion, and drawing anything beyond spaceships, I was fairly hopeless. But it did give me a base to express my creativity in a physical sense, beyond my Lego creations. But my artistic expression lay outside of the traditional forms of art. I was introduced to photography, beyond the snapshot, in an English class. A roll of black and white film, and a Pentax K1000 from the school’s photography lab was all it took. I was hooked, this was exactly what I had been looking for, so at a garage sale I found an old Minolta rangefinder and started shooting, playing with aperture, shutter speed, and of course teaching myself how everything worked. Film was my medium of choice, digital wasn’t yet an option, as most consumer grade digital cameras were still just entering the market and the costs were still high, especially for a high school student going into college and working at McDonalds. I scored a good deal on a digital camera, and soon found my film work falling by the wayside, drawn into the ease of use and near instant options that it brings. But what I didn’t expect was that it would be a detriment to my photography, losing my artistic flare, I became obsessed with the technical aspects of photography, noise, sharpness, and perfect exposure. It wasn’t really a bad thing, in fact I feel it was again a good foundation building for my work, because when I returned to film I was a much stronger photography, and the film simply brought me back to the creative aspect of the medium. I was able to create stronger images knowing the technical details and the rules, and being able to bend and break them to get my image how I imaged it, the first time. And of course remembering to slow down, take my time, and most importantly, have fun.

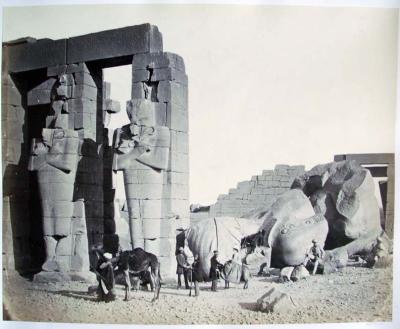

The simple answer to why I shoot film is because its fun, but you’re probably not here looking for a simple answer. Have you ever seen an 8×10 image made on slide film? I have never seen such depth, colour reproduction, or sharpness on any digital images, and it was something that I could hold in my hands. Now don’t get me wrong, I’m not knocking digital in anyways, it still holds a place within the photographic community and space, but for me, digital never really cut it. There was no tangible connection to my photos. It was an image on a screen. I feel I can create stronger images with film than I ever could with digital. It just makes me slow down, make sure everything is right, the first time, and to actually enjoy shooting and creating. It also has to do with a level of control over your images, from choosing the film, camera, lens, based on what I have already pictured in my mind first, and then choosing the things needed to create that. It becomes more than just applying filters and sliders in a computer program, but being able to do it physically, choosing the right film, then matching it with the right chemistry to process it in. It’s the perfect blend of science and art. There’s just something special about loading this thin piece of plastic into a tank, pouring in chemicals, in sequence, sloshing them around and pulling it out, and having images appear, or watching an image show up on a piece of paper that you just exposed to light behind one of those negatives. It is something that I created, starting first with my heart and mind, and then setting about creating it. That’s why I shoot film.