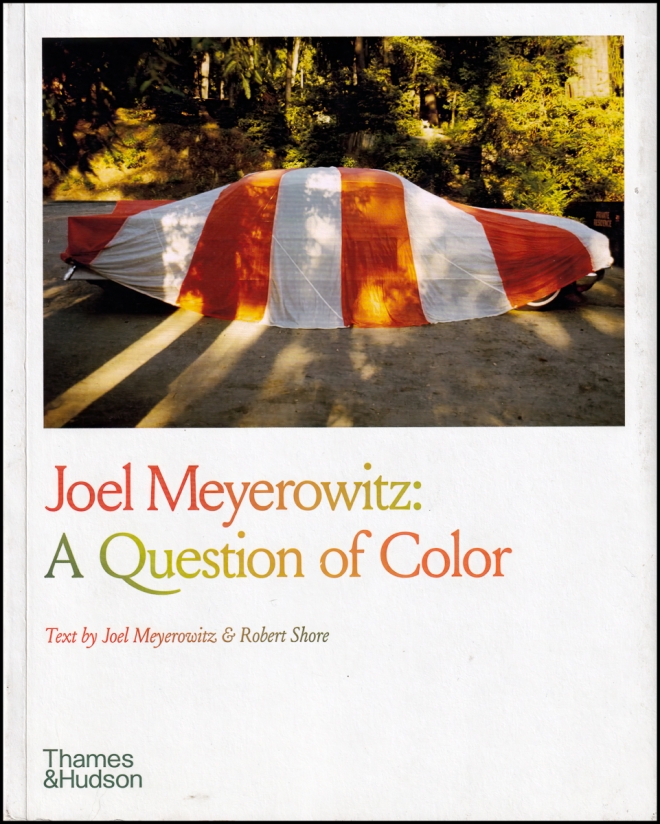

Once upon a time I didn’t care for street photography. But I’m an avid consumer of photobooks and after acquiring books by/about such luminaries as Joel Meyerowitz, Gary Winogrand, Robert Frank etc. I began to understand it better and even tried to do street photography of my own. One of the photographers I came across was Lee Friedlander. I saw some of his photographs online and liked them a lot and so decided to find out more. As is the norm for me I decided to get my hands on a book. This turned out to be harder than I thought. He’s a prolific creator of photobooks. See below for a partial list:

- The American Monument. New York: Eakins Press Foundation, 1976. ISBN 0-87130-043-5.

- Lee Friedlander Photographs. New City, NY: Self-published / Haywire Press, 1978.

- Factory Valleys: Ohio & Pennsylvania. New York: Callaway Editions, 1982. ISBN 0-935112-04-9.

- Lee Friedlander Portraits. Boston: Little, Brown, 1985. ISBN 0-8212-1602-3.

- Like a One-Eyed Cat: Photographs by Lee Friedlander, 1956–1987. New York: Harry N. Abrams in association with the Seattle Art Museum, 1989. ISBN 0-8109-1274-0.

- Nudes. New York: Pantheon, 1991. ISBN 0-679-40484-8.

- The Jazz People of New Orleans. New York: Pantheon, 1992. ISBN 0-679-41638-2.

- Maria. Washington: Smithsonian, 1992. ISBN 1-56098-207-1.

- London: Jonathan Cape, 1993. ISBN 9780224032957.

- Bellocq: Photographs from Storyville, the Red-Light District of New Orleans. New York: Random House, 1996. ISBN 0-679-44975-2.

- The Desert Seen. New York: Distributed Art Publishers, 1996. ISBN 1-881616-75-4.

- American Musicians: Photographs by Lee Friedlander. New York: Distributed Art Publishers, 1998. ISBN 1-56466-056-7. By Friedlander, Steve Lacy, and Ruth Brown.

- Lee Friedlander. San Francisco: Fraenkel Gallery, 2000. ISBN 1-881337-09-X.

- Stems. New York: Distributed Art Publishers, 2003. ISBN 1-891024-75-2.

- Lee Friedlander: Sticks and Stones: Architectural America. San Francisco: Fraenkel Gallery, 2004. ISBN 1-891024-97-3. By Friedlander and James Enyeart.

- Cherry Blossom Time in Japan: The Complete Works. San Francisco: Fraenkel Gallery, 2006. ISBN 1-881337-20-0.

- Lee Friedlander: New Mexico. Santa Fe, NM: Radius Books, 2008. ISBN 978-1-934435-11-3. By Friedlander, Andrew Smith, and Emily Ballew Neff.

- Photographs: Frederick Law Olmsted Landscapes. New York: Distributed Art Publishers, 2008. ISBN 978-1933045733.

- America by Car. San Francisco: Fraenkel Gallery, 2010. ISBN 978-1-935202-08-0.

- Portraits: The Human Clay: Volume 1. New Haven, CT: Yale University, 2015. ISBN 978-0-300-21520-5.

- Children: The Human Clay: Volume 2. New Haven, CT: Yale University, 2015. ISBN 978-0-300-21519-9.

- Street: The Human Clay: Volume 3. New Haven, CT: Yale University, 2016. ISBN 978-0-300-22177-0.

- Lee Friedlander: Western Landscapes. New Haven, CT: Yale University Art Gallery, 2016. ISBN 978-0-300-22301-9.

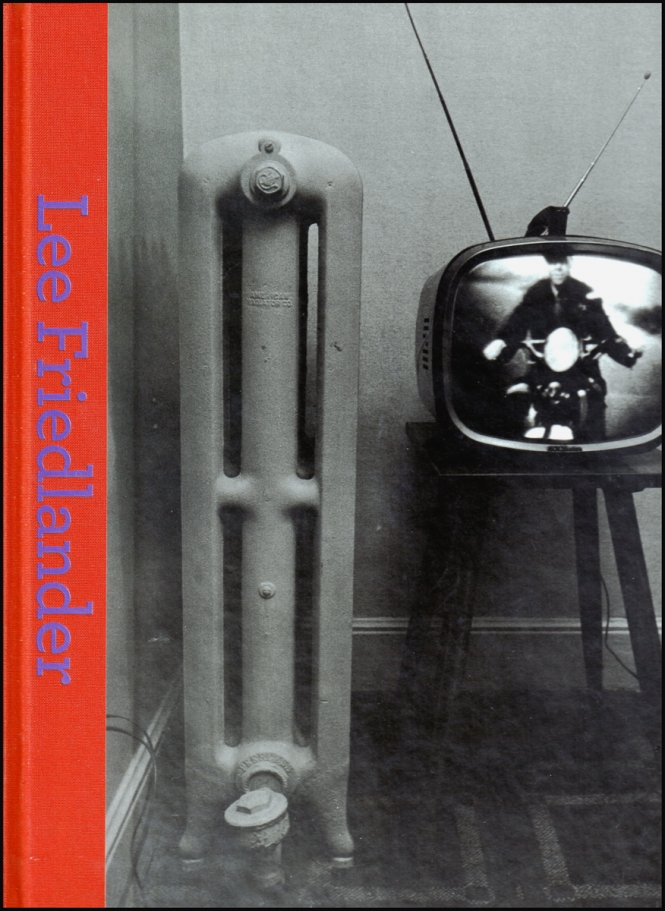

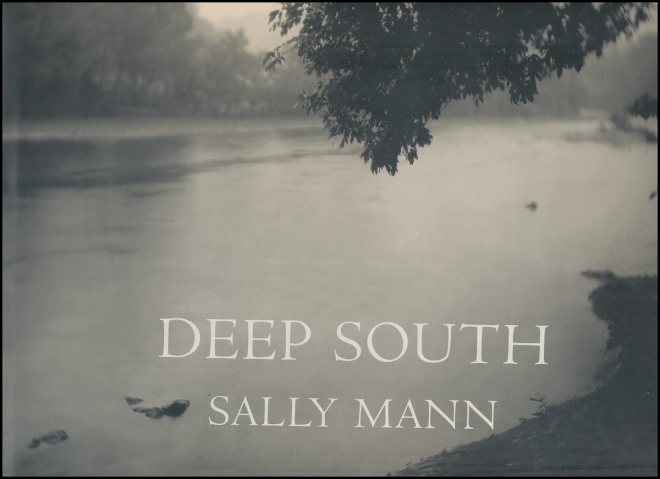

All you’ll have seen his books cover a multitude of topics. Unfortunately, that wasn’t what I wanted. I was looking for a fairly recent retrospective covering his work in general. At that time the type of book I was looking for was either out of print, extremely expensive or both. This situation now seems to have changed so when I spotted this book, I immediately acquired it.

It’s quite a large (10″ x 12″) book, which explains why the right side is cut off in the picture. It just wouldn’t fit on my admittedly small scanner.

The book is in four parts. The first is an essay by Carlos Gollonet entitled “The World According to Lee Friedlander”. I found this most informative and refreshingly free of the “critic speak” you often find in such pieces. Instead, it was rather easy to read. I found the second part, “My life with Lee. An Interview with Maria Friedlander” to be absolutely fascinating. Since Mr. Friedlander is known for his reluctance to give interviews, this might be the close as we’re going to get. The third part: “How he sees” by Nichols Nixon is short and left very little impression on me. I guess it’s a personal reflection by someone who knows Friedlander well. The third part, which takes up most of the book is called “Catalog” and contains over 300 photographs, mostly black and white, but a few in color. The book concludes with a chronology of the artist’s life by his grandson Giancarlo T. Roma.

I really enjoyed it.