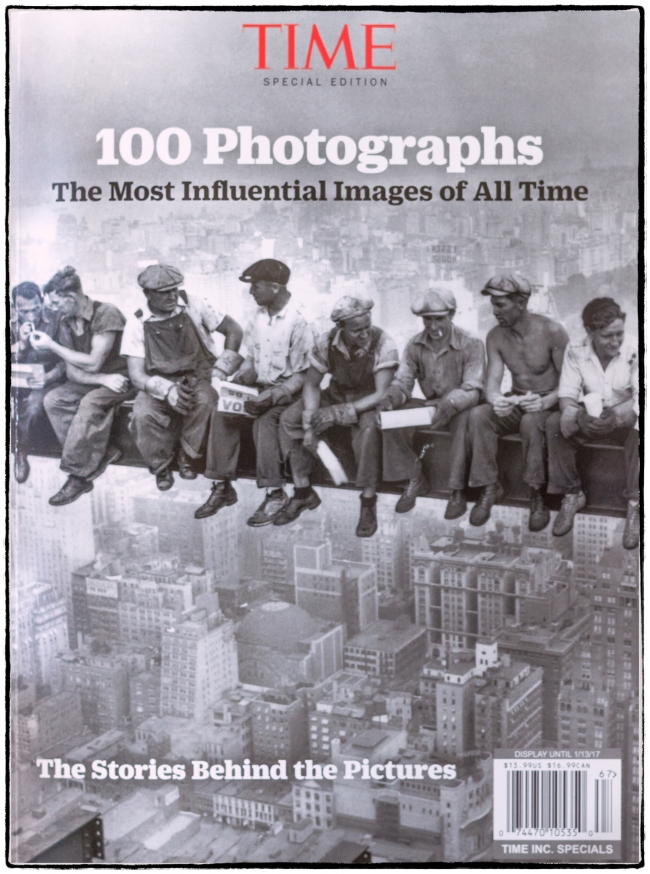

I went grocery shopping the other day and as I was standing in line at the checkout I noticed this publication. I’d read that Time was about to publish such a volume, but had then forgotten about it. It seemed like it might make an interesting read so into my cart it went.

I’m glad I got it. The subtitle is “The Stories Behind the Pictures” and I certainly found the introduction and the short textual “stories”, which accompany each picture to be of interest.

Anyone who compiles a ‘best of…’ list is looking for trouble. You can’t please everyone so there will always be complaints. Time has set itself a particularly difficult task in that it has tried to identify the ‘most influential’. They do spend some time in the introduction explaining what criteria they used and how they applied these criteria, but trying to determine influences is always hard. I couldn’t help but feel in some cases that the pictures didn’t so much ‘influence’ as much as they did just reflect an already existing trend.

In my opinion this publication also reflects a couple of biases: 1) a concentration on US photography; and 2) a preference for photojournalism/reportage. Considering the history of ‘Time’ I suppose this should be no surprise.

Of course I have my own thoughts as to what should have been included, and what not. For example – the daguerreotype was certainly very influential in the early days of photography, but ultimately turned out to be a dead end as it produced a positive image, which could not be reproduced. I could argue that Willam Henry Fox Talbot’s calotype process (and other processes which produced negatives e.g. collodion etc.) was ultimately much more influential as it formed the basis for photography for the next 150 years or so. Likewise you could make the case that, although Carleton Watkins came first and influenced the establishment of the Yosemite National Park, Ansel Adams was ultimately more influential both in terms of the environmental movement and the development of photography. But these are mere subjective quibbles that inevitably come up whenever anyone attempts a list of this kind.

Generally I liked this publication a lot and I’m glad I bought it.