Entrance to the cemetery looking from inside. A small, pleasant cemetery in the town of Southeast. You approach the cemetery along a short trail (where I saw the Dryad’s Saddle fungus). It would have been a tranquil walk if not for the close proximity to a major highway (Route 684) and the constant drone of traffic. The cemetery does not have much in the way of statuary, but there are a number of ornamental flowering shrubs, which would probably have been quite spectacular had they been in bloom – unfortunately they weren’t.

A nearby historical marker sign reads: “Drewsclift Cemetery. Daniel Drew, railroad and steamboat promoter, found of Drew Seminary and University, builder of churches buried here”. Other than that I haven’t been able to find out much about this cemetery apart from the description in Adventures around Putnam:

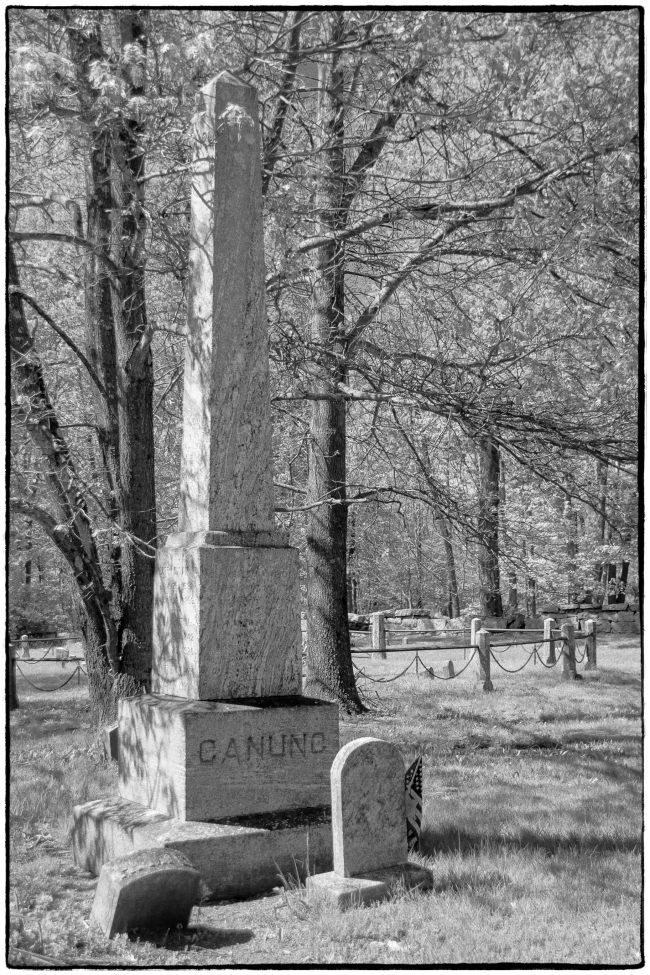

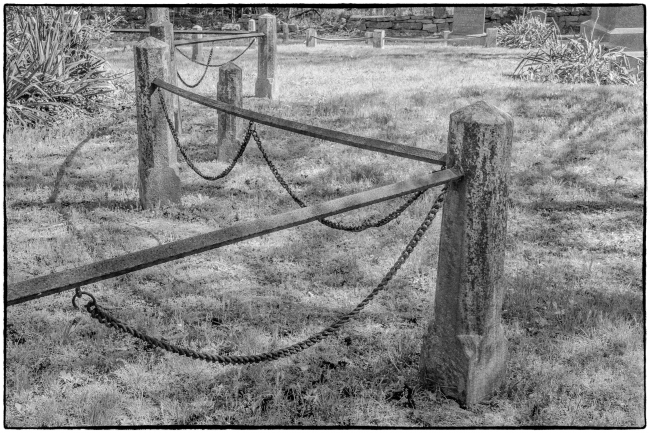

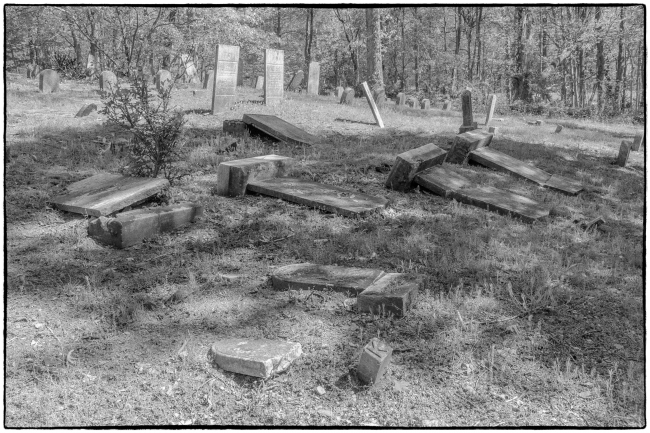

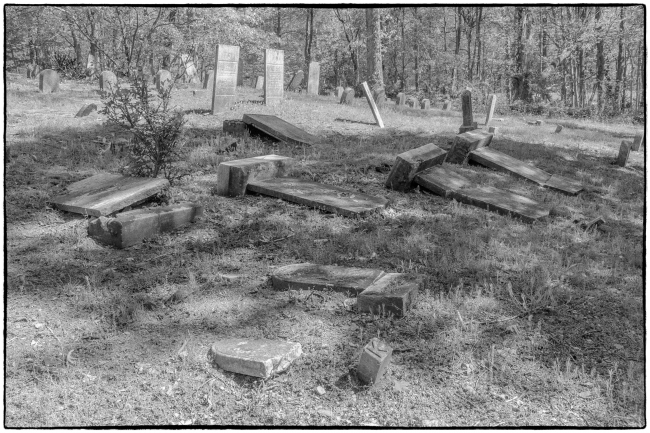

The cemetery itself has a beautiful stone wall around the perimeter, laid out in a large square. The graves and walking path form a circle within the outer square. Some of the headstones are worn and illegible, while others look like they were replaced or refurbished recently. Some are tiny, and some are grandiose. A few of the headstones have been knocked over.

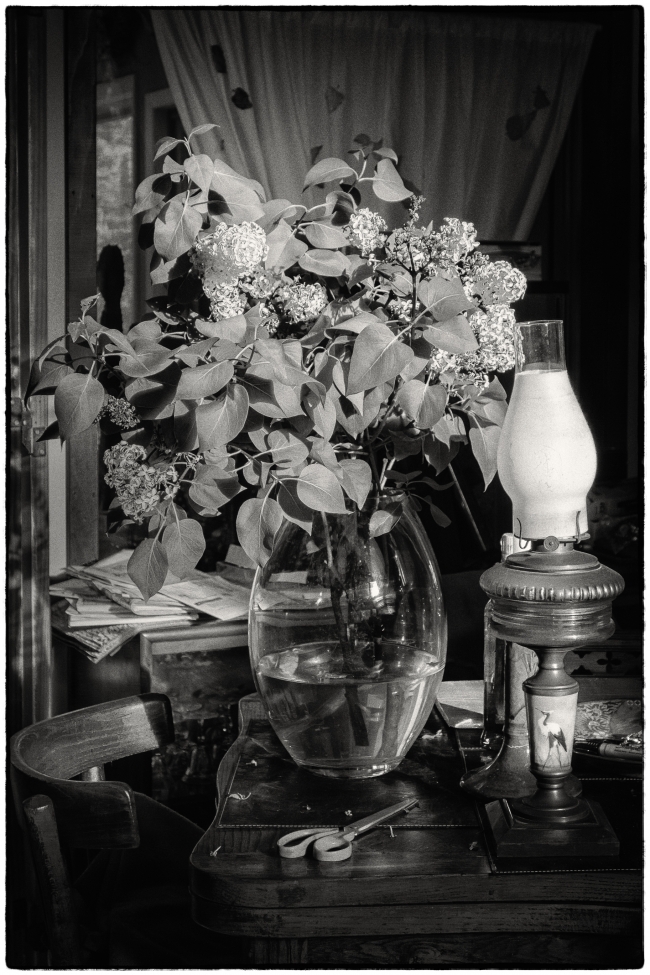

The plants and trees in the cemetery really added to the experience. Botany is not one of my strong points, so I can’t tell you what kind of plants and trees were there, but they added something ineffable to the experience.

…

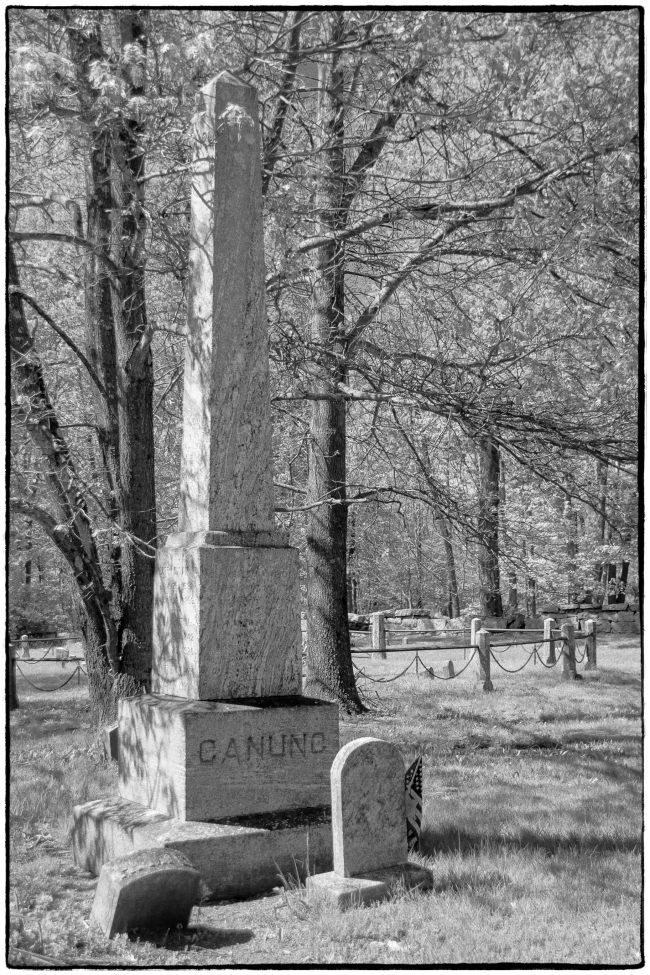

The dates on the headstones at Drewsclift range from the late 1700’s to as recent as 1961. The family names include Adams, Bailey, Clift, Drew, Mead and many others. The most notable historical figure to be buried in Drewsclift is Daniel Drew. Mr. Drew was a businessman in the 1800’s whose pursuits included cattle, stock brokerage (and stock manipulation), steamships and railways. He declared bankruptcy a few years before his death, but at one point owned almost 1000 acres in Putnam County. He was very involved with the Methodist Church, and founded the Drew Seminary.

Obelisk (of which there were a number)

Zigzag fence.

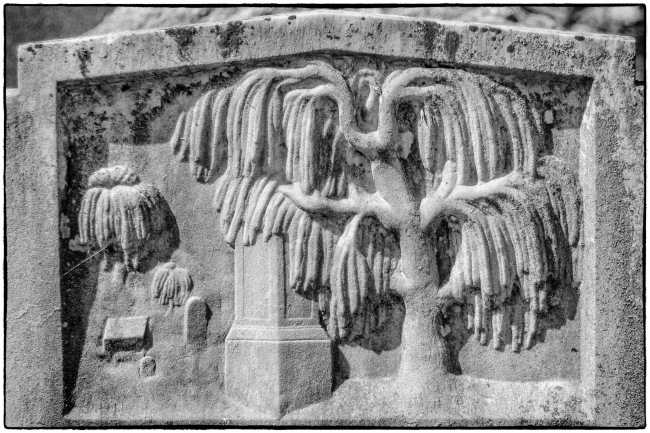

Weeping Willow motif on a gravestone. According to Engraved. The Meanings Behind Nineteenth-Century Tombstone Symbols:

Carvings of weeping willows became very prevalent on gravestones in the early 19th century. Use of this graceful symbol reflected the young United States’ growing interest in ancient Greece. Beginning in 1762 with the publishing of The Antiquities of Athens by Stuart and Revett, which produced the first accurate surveys of ancient Greek architecture, Great Britain, Europe and eventually the United States began copying Greek style in architecture and interiors. This emulation even carried over into funerary art. For the United States, the comparison between ancient Greece and its democracy with the former colonists’ “grand new experiment” in government was inspiration for copying everything Greek.

Gravestone carvers created weeping willows alone or with Greek-inspired urns, obelisks, or monuments. The most obvious meaning of a weeping willow would seem to be the “weeping” part…for mourning or grieving for a loved one. The saying “she is in her willows” implies the mourning of a female for a lost mate. And while the Victorians took the art of mourning to new heights, the weeping willow was not just a symbol for sadness.

…

[In Ancient Greece] It was common to place willow branches in the coffins of the dead, and then plant young saplings on their graves, with the belief that the spirit of the dead would rise up through the tree.

Fallen gravestones.