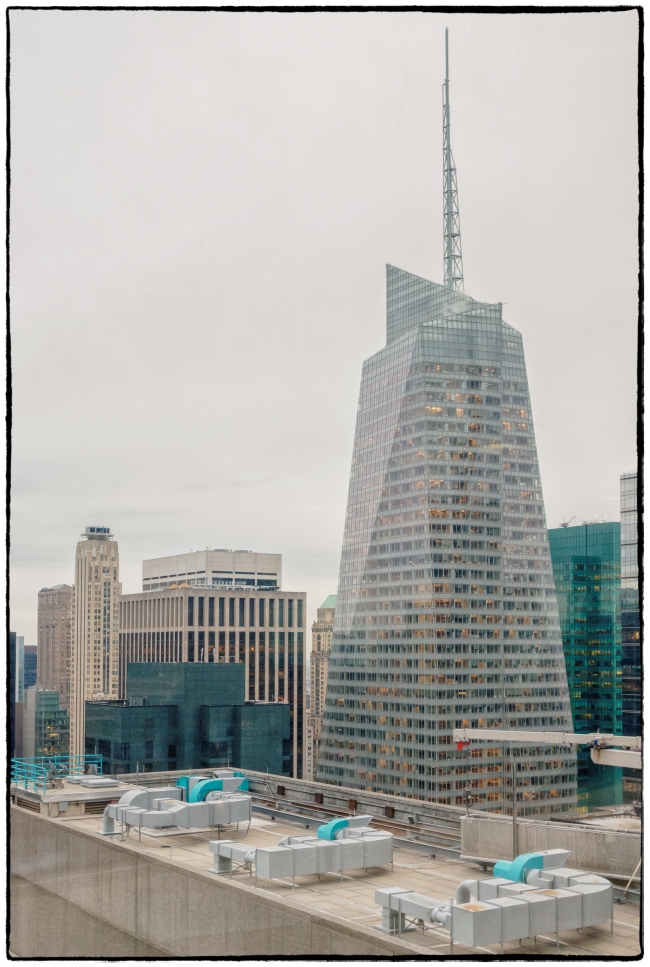

I’ve seen this spectacular building many times from street level, and have even photographed it. Seen from up high it looks completely different – especially since the other buildings obstruct the view and you can only see the upper part.

The Bank of America Tower at One Bryant Park was designed to set a new standard in high-performance buildings, for both the office workers who occupy the tower and for a city and country that are awakening to the modern imperative of sustainability. Drawing on concepts of biophilia—or humans’ innate need for connection to the natural environment—the vision at the occupant scale was to create the highest quality modern workplace by emphasizing daylight, fresh air, and an intrinsic connection to the outdoors. At the urban scale, the tower addresses its local environment as well as the context of midtown Manhattan, to which it adds an expressive new silhouette on an already-iconic skyline.

The building responds to the dense urban context by weaving into the existing grid at street level, yet challenging the boundaries of public and private space with a highly transparent corner entry. As it rises, the tower shears into two offset halves, increasing the verticality of its proportions as well as the surface area exposed to daylight. Mass is sliced from these two rectilinear volumes, producing angular facets that open up light and oblique views beyond the typical limits of urban geometry. The crystalline form—inspired by the legacy of the 1853 Crystal Palace, which once stood adjacent in Bryant Park, and by a quartz crystal from the client’s collection—suggests an appropriate natural analogue, both organic and urban in nature. With its crisp, folded façade, the tower changes with the sun and sky; its southeast exposure, a deep double wall, orients the building in its full height toward Bryant Park, its namesake and the most intensively-used open space in the US.

With the Bank of America as its primary tenant, occupying six trading floors and 75% of its interior, the tower signals a significant shift in corporate America and in the real estate industry, acknowledging the higher value of healthy, productive workplaces. One Bryant Park’s most lasting achievement is to merge the ethics of the green building movement with a twenty-first century aesthetic of transparency and re-connection.

Bank of America Tower is the first commercial high-rise to earn LEED Platinum certification from the US Green Building Council. The building’s advanced technologies include a clean-burning, on-site, 5.0 MW cogeneration plant, which provides approximately 65% of the building’s annual electricity requirements and lowers daytime peak demand by 30%. A thermal storage system further helps reduce peak load on the city’s over-taxed electrical grid by producing ice at night, melted during the day to provide cooling. Nearly all of the 1.2m (4ft) of annual rain and snow that fall on the site is captured and re-used as gray water to flush toilets and supply the cooling towers. These strategies, along with waterless urinals and low-flow fixtures, save approximately 7.7 million gallons of potable water per year.

Recycling was a prominent factor throughout the building’s construction, with 91% of construction and demolition waste diverted from landfill. Materials include steel made from 75% (minimum) recycled content and concrete made from cement containing 45% recycled content (blast furnace slag). To protect indoor air quality as well as natural resources, interior materials are low-VOC, sustainably harvested, manufactured locally, and/or recycled wherever possible.

The building’s exceptionally high indoor environmental quality results from hospital-grade, 95% filtered air; abundant natural daylight and 2.9m (9.5ft) ceilings; an under-floor ventilation system with individually-controlled floor diffusers; round-the-clock air quality monitoring; and views through a clear, floor-to-ceiling glass curtain wall. This high-performance curtain wall minimizes solar heat gain through low-E glass and heat-reflecting ceramic frit; it also has allowed the Bank of America Tower to reduce artificial lighting with an automated daylight dimming system, reducing lighting and cooling energy by up to 10%.

On an urban level, the project also represents the culmination of the developer’s multigenerational efforts to revitalize the Times Square area, and gives back to the city with a street-level Urban Garden Room, a mid-block pedestrian passage/performance space, and the first “green” Broadway theater, the LEED Gold Stephen Sondheim Theater.

In an era of heightened security, a central challenge of the project was balancing the complexities of program and scale with high-performance architecture and urban design. In its layered connection to the ground plane, Bank of America Tower resolves this question with a progression of public and private spaces—from Bryant Park to the Urban Garden Room to the semi-public lobby. As a total response to the urban environment, the building’s restorative connections therefore work on many levels, from green roofs and views of the park to more subtle and expressive elements. A highly integrated approach to architecture and engineering ensured a close relationship between form and function. Bridging contexts as vastly different as Times Square and Bryant Park, the project makes a highly visible statement on urban stewardship and global citizenship for the 21st century

Taken with a Sony RX-100 M3.