In first paragraph of his introductory essay, “Collective Memories in Kodachrome”, Richard B. Woodward writes:

A young woman is seated on the edge of a blue Adirondack chair. A thin and expensive yellow sweater draped over her shoulders and bare arms, she wears a high-necked black dress and holds a cigarette in her right hand. Her icy hauteur might have caught the eye of Alfred Hitchcock, who could have cast her as the threatened heroine’s younger sister. The Anonymous Project is a collection of similar scenes – the sweet, awkward, random moments that no one recalls now unless someone had recorded them in a photograph.

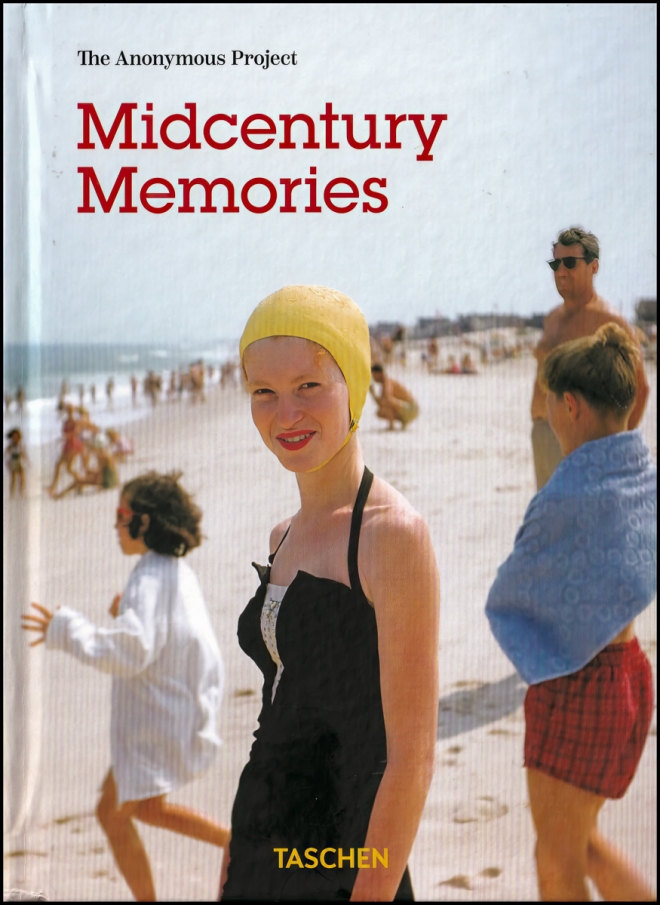

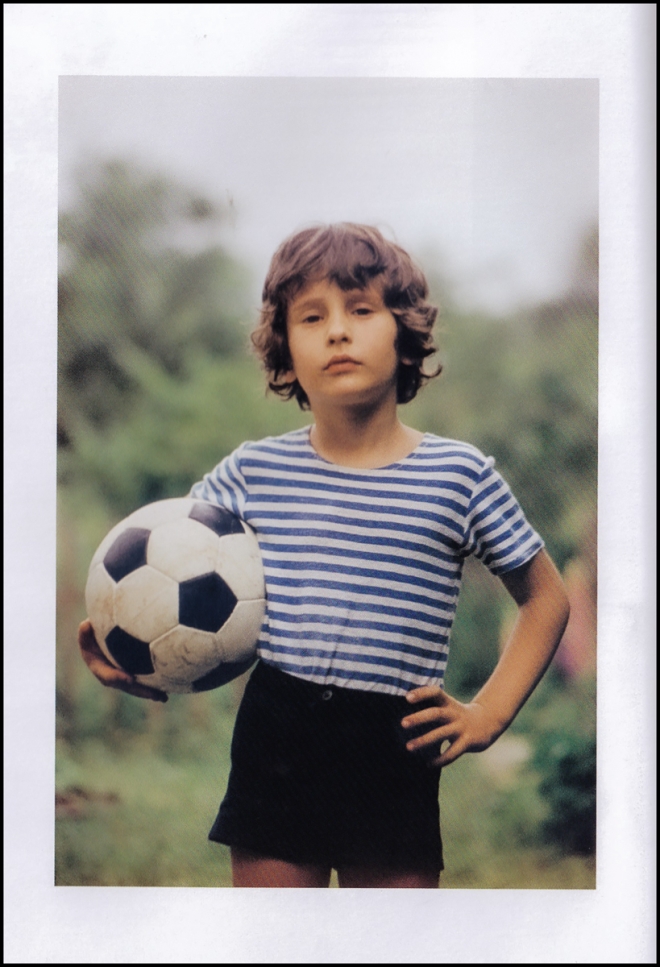

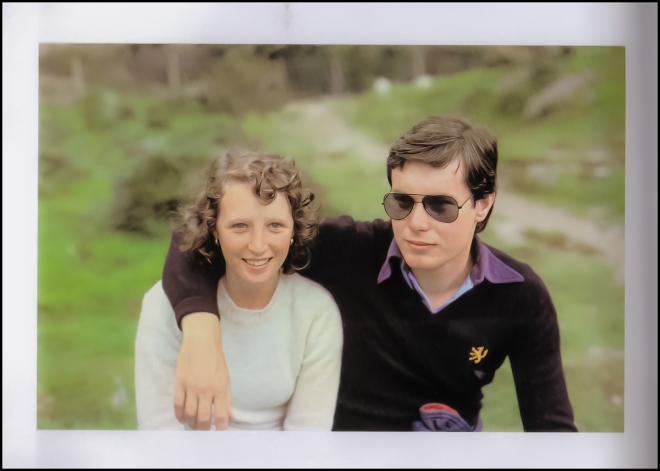

And that’s pretty much what this book is. Apart from this essay at the beginning, and a brief interview with the founder and creative director of The Anonymous Project at the end, that’s pretty much it: about 140 or so pages of anonymous photographs (a small sample below) derived from Kodachrome Slides.

I was never much into slide photography. As Woodward writes:

The downside was that slides were much easier to make than to look at. Once they came back from development by Kodak or Agfa or Ilford or Fuji, it was not clear what to do with them. You couldn’t paste transparencies in a photo album or put them on your desk at the office…But the only chance most had to review how well (or poorly) they had photographed something in Kodachrome or Ektachrome was by setting up a slide projector…In the 1950s and ’60s, as projectors entered middle-class American and European homes and school classrooms, the slide show became a group activity, and more often than not a coerced one under the dictatorship of a parent or teacher.

The person in the family hierarchy who organized the trays or held the remote control – the role of photographer in chief was usually the father’s – would set the order and the pace, which was often agonizingly slow with long pauses for commentary. The slides themselves had no afterlife beyond their one-night-only appearance in a living room or den. Most disappeared back into their cardboard boxes and never saw daylight again. Shulman estimates that many of the images in his book have not been viewed by anyone, even by those to whom they once belonged, for 60 years.

I agree with most of what he writes, but not that they were “easier to make than to look at”. On my very rare forays into slide photography, I found it extremely difficult to get them right.

However, as I look at the photographs in the book, I can’t help but feel that maybe I should have tried harder. The pictures really are very bright and colorful.

I have a feeling that the quality of the photographs in the book are somewhat better than your average snapshot. Could this be because the process of making and showing slides was so cumbersome that only more dedicated photographers did it?

Good book though, I enjoy picking it up and browsing through it from time to time…and wondering who the people in the slides were, and what happened to them.