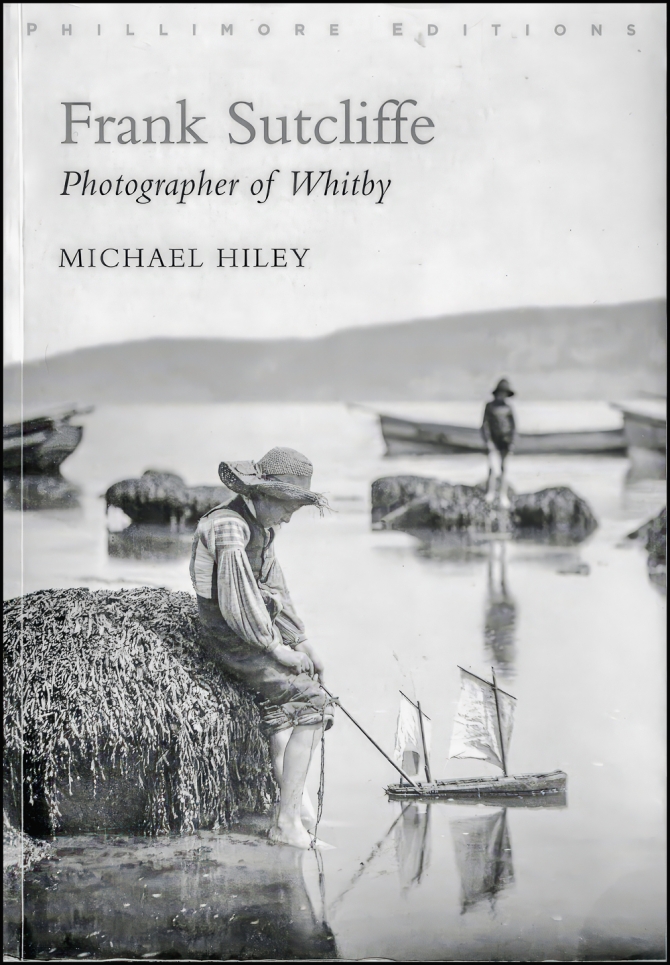

Niceart gallery describes Frank Sutcliffe as follows:

Frank Meadow Sutcliffe stands as a pivotal figure in the history of photography, a practitioner whose lens captured not just images, but the very essence of late Victorian and early Edwardian life in the English coastal town of Whitby. His work, characterized by a profound naturalism and an empathetic eye, transcended mere documentation, elevating everyday scenes to the realm of art. Sutcliffe was more than a local photographer; he was an innovator, a theorist, and a key participant in the international movement to establish photography as a legitimate artistic medium. His legacy endures through his evocative images and his contributions to the discourse of photography.

Early Life and the Call of the Camera

Born on October 6, 1853, in Headingley, Leeds, Frank Meadow Sutcliffe was the eldest of eight children born to Thomas Sutcliffe, a respected painter, etcher, and art lecturer. This artistic household undoubtedly nurtured young Frank’s visual sensibilities. His father, recognizing his son’s burgeoning interest, provided him with his first camera. The elder Sutcliffe’s connections in the art world, which included figures like John Ruskin, may have also subtly influenced Frank’s aesthetic development, instilling an appreciation for truthfulness in representation, a quality that would later define his photographic style.

Tragedy struck the family when Thomas Sutcliffe passed away in 1871. At the young age of eighteen, Frank found himself shouldering significant family responsibilities. The necessity of earning a living became paramount. While he had an artistic grounding, the path of a painter was precarious. Photography, then a burgeoning field, offered a more practical, albeit still challenging, avenue. He made the decisive choice to pursue photography professionally, a decision that would shape his life and contribute significantly to the medium’s history. His initial foray into professional photography involved working for Francis Frith, a prominent commercial photographer known for his extensive views of the UK and the Middle East. This experience likely provided valuable technical and business insights.

Whitby: A Muse in Stone and Sea

In 1875, seeking to establish his own practice, Sutcliffe moved to the bustling fishing port of Whitby on the Yorkshire coast. This town, with its dramatic cliffs, ancient abbey, winding cobbled streets, and vibrant maritime life, would become his lifelong muse. His first studio in Whitby was a modest affair, ingeniously set up in a disused jet worker’s shop in Waterloo Yard. Jet, a black lignite, was a significant local industry, and its workshops were part of the town’s fabric. Later, he would move to a more conventional studio on Skinner Street, which became a well-known local landmark.

Whitby offered an inexhaustible supply of subjects. Sutcliffe was captivated by the hardy fisherfolk, their weathered faces telling tales of the sea. He documented their daily toil: mending nets, baiting lines, hauling catches, and navigating the harbour. His lens also captured the town’s architecture, the dramatic coastal landscapes, and the leisurely pursuits of its inhabitants and visitors. He was not merely recording; he was interpreting, seeking the inherent beauty and character in the ordinary. His deep affection for Whitby and its people shines through in his extensive body of work, creating an invaluable historical and social record.

The Naturalistic Vision: Style and Philosophy

Sutcliffe’s photographic style is best described as naturalistic. He aimed for a truthful, unembellished representation of life, eschewing the artificiality and sentimentality that characterized much Victorian art photography. His approach was deeply influenced by the theories of Peter Henry Emerson, a contemporary photographer and writer who championed “Naturalistic Photography.” Emerson advocated for images that were true to nature and human perception, often focusing on rural life and landscapes, and encouraging differential focusing to mimic human vision. Sutcliffe embraced this ethos, striving for spontaneity and authenticity in his compositions.

His work also shows an affinity with the French Realist painters of the mid-19th century, such as Jean-François Millet and Gustave Courbet, who depicted ordinary people and their labor with dignity and honesty. Like these painters, Sutcliffe found artistic merit in the everyday. He possessed a remarkable ability to capture fleeting moments, gestures, and expressions that conveyed the personality of his subjects and the atmosphere of the scene. His compositions, while appearing unposed, were often carefully considered, demonstrating a sophisticated understanding of light, form, and balance. He masterfully used the soft, diffused light of the North Yorkshire coast to create atmospheric and evocative images.

Landmark Works and Their Echoes

Among Sutcliffe’s most iconic photographs is “Water Rats,” taken in 1886. The image depicts several naked young boys playing around and in a boat in Whitby Harbour. While today it is celebrated for its candid charm and evocation of carefree childhood, in its time, it courted controversy. Victorian sensibilities were easily offended by public nudity, even in an innocent context. Sutcliffe defended the work, asserting its artistic intent and lack of prurience. The local clergy reportedly condemned it, and one story suggests a print was even ordered to be burned. Despite, or perhaps because of, the controversy, “Water Rats” became one of his most famous images, winning a medal at the Photographic Society of Great Britain’s exhibition.

His harbor scenes, often simply titled “Whitby Harbour” or with descriptive titles like “Excitement” (depicting a crowd awaiting a ship), are masterpieces of atmospheric rendering. He skillfully captured the interplay of light on water, the silhouettes of boats against a misty sky, and the bustling activity of the quayside. These images convey a strong sense of place and time. Portraits of local characters, such as fishermen, jet workers, and farm laborers, are also a significant part of his oeuvre. These are not stiff, formal studio portraits but rather intimate studies of individuals in their familiar environments, their character etched into their faces and posture. Works like “Stern Realities” or “Monday Morning” exemplify this empathetic portrayal of working life.

Technical Prowess in a Demanding Era

Sutcliffe worked primarily with large, cumbersome whole-plate cameras, typically made of brass and mahogany. These cameras used glass plate negatives, often 8.5 x 6.5 inches or larger, which required considerable skill to handle and process. The photographic emulsions of the time were slow, necessitating relatively long exposure times. This meant that capturing “spontaneous” moments required remarkable anticipation and an ability to direct subjects subtly without them appearing stiff or posed.

He was a master of the collodion process and later, dry plates, which offered more convenience. Sutcliffe favored platinum prints (platinotypes) and carbon prints for their rich tonal range and permanence, processes favored by art photographers of the era. He was known for his direct printing methods, largely avoiding the extensive retouching and composite printing techniques employed by some of his contemporaries, such as Henry Peach Robinson in his earlier, more allegorical works, or Oscar Gustave Rejlander. Sutcliffe believed in the inherent truthfulness of the photographic image, allowing the subject and the light to speak for themselves. His technical skill was not an end in itself but a means to achieve his artistic vision.

A Wider Influence: The Camera Club, The Linked Ring, and International Acclaim

Sutcliffe was not an isolated provincial photographer. He was actively involved in the broader photographic community and played a significant role in the debates and movements of his time. He was a founding member of The Camera Club in London, a society established in 1885 for amateur photographers interested in the artistic and scientific aspects of the medium. His involvement here connected him with other forward-thinking photographers.

His most significant affiliation was with the Linked Ring Brotherhood, an international group of art photographers founded in 1892. This influential society seceded from the more conservative Photographic Society of Great Britain (later the Royal Photographic Society) to promote photography as a fine art – a movement known as Pictorialism. Sutcliffe was a founding member, joining ranks with other prominent figures like Henry Peach Robinson (who had by then evolved his style), George Davison, Frederick H. Evans, and James Craig Annan from Scotland. The Linked Ring organized influential annual exhibitions, known as the Photographic Salon, which showcased the best of international pictorial photography, including works by Alfred Stieglitz, Edward Steichen, Gertrude Käsebier, Clarence H. White from America, and Robert Demachy from France.

Sutcliffe’s own work gained considerable international recognition. He exhibited widely and won over sixty medals and awards from photographic societies and exhibitions around the world, including prestigious accolades from Paris, Vienna, New York, Calcutta, and Tokyo. In 1888, he was honored with one of the earliest solo exhibitions for a photographer, held at the gallery of the Photographic Society of Great Britain, a testament to his growing stature. He was also a prolific writer on photography, contributing articles and a regular column, “Photography Notes,” to the Yorkshire Weekly Post and other photographic journals. Through his writings, he shared his technical knowledge, aesthetic ideas, and humorous observations on the life of a photographer.

Later Years, Curatorship, and Enduring Legacy

As the 20th century progressed, photographic tastes and technologies evolved. While Sutcliffe continued to photograph, the peak of his creative output is generally considered to be the period from the 1880s to the early 1900s. He adapted to changing times, even undertaking commercial work like postcard views of Whitby to sustain his business. His deep connection to Whitby and its history found a new outlet in his later years. In 1922, he was appointed curator of the Whitby Literary and Philosophical Society’s Museum and Art Gallery, a position he held with dedication until shortly before his death. This role allowed him to continue contributing to the cultural life of the town he so dearly loved.

Frank Meadow Sutcliffe passed away on May 31, 1941, at the age of 87, in his home in Sleights, near Whitby. He left behind an extraordinary archive of thousands of negatives, a rich visual tapestry of a bygone era. His contributions to photography were formally recognized when he was made an Honorary Fellow of the Royal Photographic Society in 1935, a fitting tribute to a lifetime dedicated to the art.

His photographs are more than just historical documents; they are works of art that continue to resonate with viewers today. They offer a window into the soul of Victorian and Edwardian Whitby, capturing its people, its industries, and its unique atmosphere with unparalleled sensitivity and skill. Sutcliffe’s commitment to naturalism, his technical mastery, and his profound empathy for his subjects place him firmly in the pantheon of great photographers. His influence can be seen in the work of later documentary photographers and those who seek to find art in the everyday. Figures like John Thomson, with his “Street Life in London,” shared a similar documentary impulse, though Sutcliffe’s work often carried a more pronounced pictorial sensibility. Even photographers like Julia Margaret Cameron, known for her allegorical and soft-focus portraits, shared with Sutcliffe the ambition to elevate photography to an art form, albeit through different stylistic means.

Conclusion: The Unwavering Gaze

Frank Meadow Sutcliffe’s enduring legacy lies in his remarkable ability to fuse documentary truth with artistic vision. He was a pioneer who not only chronicled the life of a specific English town with unparalleled depth but also championed photography’s status as a fine art on an international stage. His images of Whitby’s fisherfolk, bustling harbour, and quiet rural scenes are imbued with a timeless quality, speaking to universal human experiences of labor, community, and the simple beauty of the everyday. Through his unwavering gaze and profound understanding of his medium, Sutcliffe created a body of work that remains a touchstone for photographers and a treasure for art historians and anyone captivated by the rich tapestry of the past. His photographs are a testament to a life lived through the lens, a life dedicated to capturing the fleeting moments that define our shared humanity. The Sutcliffe Gallery in Whitby continues to preserve and exhibit his work,

I loved this book. Physically it suits me. Many of my photobooks are huge and heavy. This one is small and quite light: easy to hold and to read. It’s divided into three parts: 11 chapters outlining Sutcliffe’s life and the evolution of his art; 64 wonderful black and white plates of his work – just the photographs unencumbered by captions or descriptions; Notes to the plates. For each plate there’s a small thumbnail of the plate in question accompanied by a short summary providing additional information on.

The text in the first part includes many fascinating quotations from Sutcliffe’s monthly column, “Photography Notes,” for the Yorkshire Weekly Post from 1908 to about 1930. He also contributed articles to many newspapers and magazines, Amateur Photography among them. It’s amazing how little things have changed. Sutcliffe was not the first photographer to react against the general belief that photographs should be as clear and sharp as possible, and show as much detail as the camera and its lens would allow: For example, William Frederick Lake Price wrote:

“From a want of knowledge of the principles of art in many photographers a morbid admiration and reverence of unnaturally minute definition tends to lead the operator away from what should really be the end aim of his study. Instead of ‘going in’ for the broad vigorous effects of light and shade in the landscape he is led to look upon a mechanical ‘organ grinding’ kind of exposure consequent upon absurdly reduced aperture as the correct thing, whilst to the eye of the artist the much-vaunted result appears like a landscape carefully black-leaded, and then executed in minute needlework, qualities which are no compensation for the want of the broad and vigorous effects of light and shade which have been given by the lens when skilfully applied to this class of subject.”

The above was written in 1868. Sound very much like the current obsession with pixel peeping sharpness doesn’t it. I wonder what they would have thought of focus stacking?

I loved this book. I can’t remember when I’ve enjoyed a book so much. When I came to the end I was genuinely disappointed that there wasn’t more.