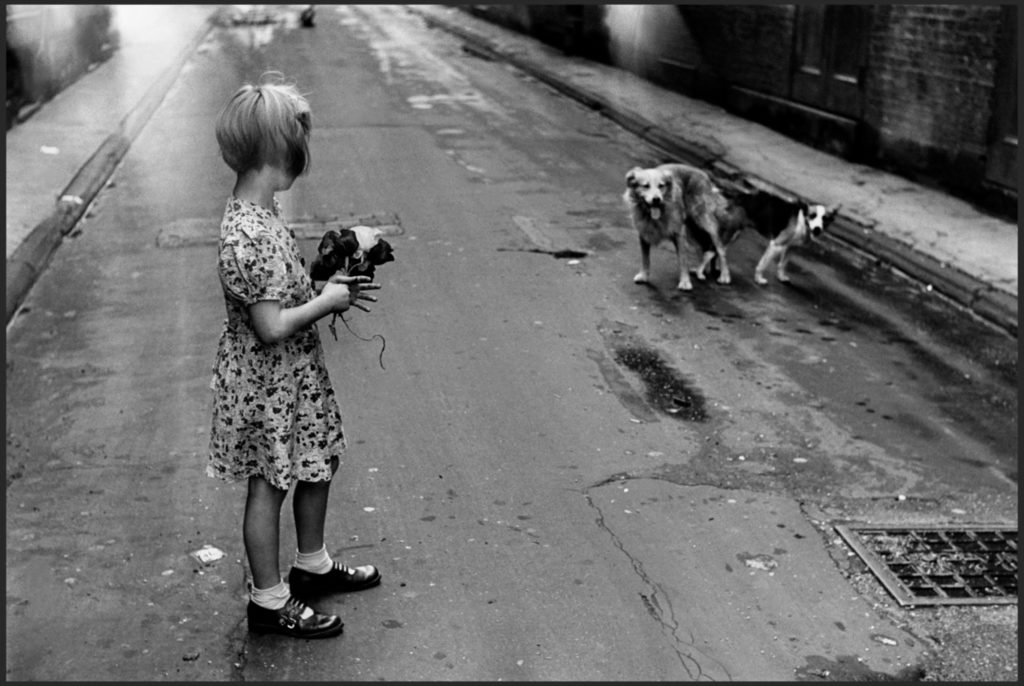

Almost a year ago (Novemeber 14, 2016 to be precise) I came across Robert Capa’s Grave in a nearby cemetery (See: Amawalk Hill Cemetery – The Big Surprise). Capa was, of course, a photographic “great”, possibly the best known of all war photographers. I was familiar with some of his work (e.g. the Normandy pictures, an example of which appears above; Falling Soldier etc.), but beyond that didn’t know much other than that he was killed in Vietnam in 1954 after stepping on a land mine.

So I decided to find out more, and after looking around for a bit came across this book, which I promptly ordered. It arrived and seems to have been promptly moved downstairs (I suspect tidied away at the request of my wife when we had visitors). So “out of sight, out of mind” I forgot that I had it until the other day when some reference to Capa made me think of it. I pulled it out and read through it.

The book is the brainchild of Cornell Capa (himself a renowned photographer and founder of the International Center of Photography and Richard Whelan – interestingly they are both buried next to Robert Capa in Amawalk Hill Cemetery).

Robert Capa grave site in Amalwalk Hill Cemetery. From left to right: David Richard Whelan (biographer); Edith Capa (wife of Cornell Capa); Cornell Capa; Julia Friedman Capa (mother of Robert and Cornell); Robert Capa).

In a section entitled “About the Photographs” Cornell Capa says the following:

Between 1990 and 1992, Richard Whelan and I rexamined all of Robert Capa’s contact sheets. From the approximately 70,000 negative frames that my brother exposed during his lifetime, we chose 937 images to constitute an in-depth – though certainly not exhaustive – survey of his finest work over the entire course of his career, from 1932 to 1954. The images are arranged here by photographic story and in chronological order, tracing the trajectory of his life. Nearly half of the 937 images have never been widely published or exhibited. Our principal goal was to identify images whose emotions and graphic impact measures up to, or at least comes close to, the impact of Capa’s classic photographs. In a very few cases, however, we included less powerful photographs in order to give coherence to a group of pictures that work together as a story, but which would not necessarily hold up as individual images.

Whelan provides an interesting, illustrated 11 page introduction and the rest of the book is devoted to the photographs, each with a usually short, quite dry caption. I much preferred the longer, more descriptive captions in Karsh. A Biography in Images. The photographs are, for the most part, wonderful, but there are so many that it’s all a bit overwhelming. This has had a few negative consequences: many of the photographs are quite small; and the book is rather large and heavy. As I usually read while sitting in a chair or on the sofa I found it quite difficult to hold comfortably. It’s more suited to reading on a stand on a table. I also found the typeface used to be hard to read. It’s a typewriter style font, and at times, when a lighter text is used, it tends to blend into the background.

I’d also take exception to Cornell Capa when he says “In a very few cases, however, we included less powerful photographs…”. I’d say that quite a few “less powerful photographs” have been included. Of course I’d have been proud to have produced any of them, but a lot of the photographs are not close to his best (just goes to show that even the greatest photographers don’t always produce winners).

I’m sure that there are books on Capa out there that include fewer photographs and consequently are more focused and easier to hold and to read. For potential readers who just want to know a bit more about Capa, I’d recommend one of those (maybe even his own memoir Slightly Out of Focus – although this seems to focus on the WWII period and so might leave out some of the wonderful Spanish Civil War pictures.). Since this volume is mostly about Capa’s pictures it might also be worth reading a biography, such as the one written by Richard Whelan: Robert Capa: A Biography.

Despite the issues noted above, I very much enjoyed this book. I feel sure that I’ll return to it from time to time to look again and again at the photographs, each time getting new insights and a better understanding.