Taj Mahal and train in Agra, 1983. Credit Steve McCurry

In McCurry’s portraits, the subject looks directly at the camera, wide-eyed and usually marked by some peculiarity, like pale irises, face paint or a snake around the neck. And when he shoots a wider scene, the result feels like a certain ideal of photography: the rule of thirds, a neat counterpoise of foreground and background and an obvious point of primary interest, placed just so. Here’s an old-timer with a dyed beard. Here’s a doe-eyed child in a head scarf. The pictures are staged or shot to look as if they were. They are astonishingly boring.

I was quite angry when I first saw this article, but I’ve calmed down now and can perhaps be a bit more balanced. I’m not the world’s biggest fan of Steve McCurry. I find his pictures a little too oversaturated for my taste. However, to go after him the way the author of this article does is, I think, going too far. I come across this kind of attitude far too much: I don’t like his pictures all that much so I’m going to call them “astonishingly boring”.

Now I’m not at all sure that I like the pictures he prefers:

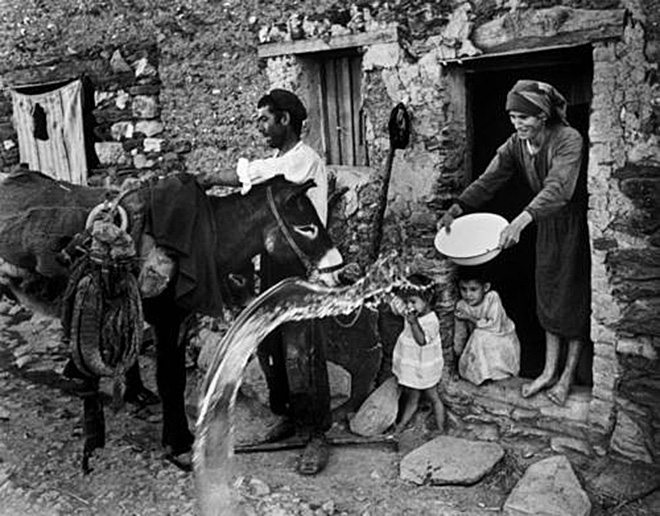

Kemps Corner, Mumbai, 1989. Credit Succession Raghubir Singh

I love even more a photograph Singh made in Mumbai a couple of years later. Taken in a busy shopping district called Kemps Corner, this photograph has less-obvious charms. The picture is divided into four vertical parts by the glass frontage of a leather-goods shop and its open glass door, and within this grid is a scatter of incident. The main figure, if we can call her that, is a woman past middle age who wears a red blouse and a dark floral skirt and carries a cloth bag on a string. She is seen in profile and looks tired. Beyond her and behind are various other walkers in the city, going about their serious business. An overpass cuts across the picture horizontally. The foreground, red with dust, is curiously open, a potential space for people not yet in the picture. The glass on the left is a display of handbags for sale, and the peculiar lighting of the bags indicates that Singh used flash in taking the shot. The image, unforgettable because it stretches compositional coherence nearly to its snapping point, reminds me of Degas’s painting “Place de la Concorde,” another picture in which easy, classically balanced composition is jettisoned for something more exciting and discomfiting and grounded.

But that’s OK. There are other famous photographers whose work doesn’t really appeal to me at this point. Maybe it will in the future – it wouldn’t be the first time e.g. at first I didn’t respond to Lee Friedlander‘s work, but after some study I now find that I like it. As the saying goes “Beauty is in the eye of the beholder”. You don’t have to like everything but please don’t denigrate things just because YOU don’t like them. By all means say you don’t like the work but why resort to “astonishingly boring”; “pictures staged”; “cliché”; “Weaker photography delivers a quick message — sweetness, pathos, humor — but fails to do more. But more is what we are” etc.

Of course he’s entitled to his opinion, but why the venom? I think the clue is in the paragraph:

How do we know when a photographer caters to life and not to some previous prejudice? One clue is when the picture evades compositional cliché. But there is also the question of what the photograph is for, what role it plays within the economic circulation of images. Some photographs, like Singh’s, are freer of the censorship of the market. Others are taken only to elicit particular conventional responses — images that masquerade as art but fully inhabit the vocabulary of advertising. As Justice Potter Stewart said when pressed to define hard-core pornography in 1964, “I know it when I see it.”

I think there are two points here: 1) Mr. McCurry is undoubtedly rich and famous and the author of the article clearly doesn’t like it; and 2) There’s something of the “real artists should be poor and living in a garret” line of thinking i.e. anything that makes money is bad. Edward Steichen had the same problem. I don’t subscribe to this view. Take Picasso for example. Definitely quite rich (his net worth at his death in 1973 was estimated to be around $50 million) yet few would dispute the artistic merit of his work.

Finally I also detect echoes of a familiar theme here: Social documentary photography has assumed immense significance and with it a sense that a photograph should always be some kind of “social statement”. This means that other genres are necessarily bad. Landscape photography – bad!; Flower photography – bad!; Wildlife photography – bad! I’ve said before that I don’t believe that Monet’s waterlilies make any kind of “social statement” (other than that Monet was well enough off to afford a big house in Giverny with extensive gardens and water features). Doesn’t stop his paintings from being art though. I guess this guy doesn’t like Weston‘s peppers or Adams‘ landscapes either.

Source: A Too-Perfect Picture – The New York Times