I’d taken the dog for a walk at the Ward Pound Ridge Reservation. After exploring the park for a while I was returning to the car when, looking at the map, I noticed a symbol marked ‘cemetery’. I’m fond of old cemeteries so even though I was hot and tired I made a short side trip to take a look.

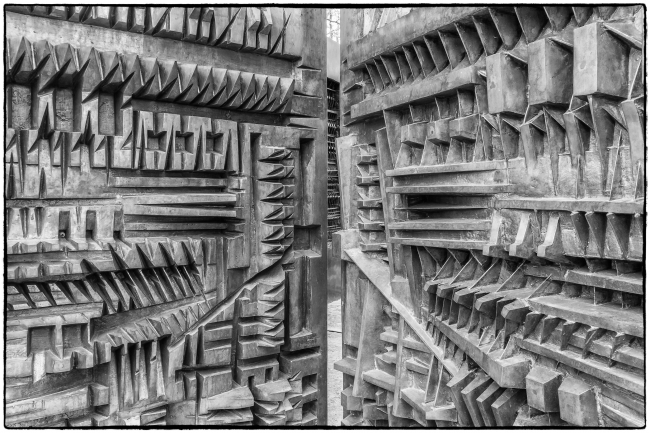

A nearby panel says:

This cemetery was inventoried in 2009 by Garrett Kennedy as part of his Eagle Project. The earliest inventory on record was done in 1941 by Mrs. Sterling B. Jordan and Mrs. Frank W. Seth. In 1942 there were 187 head stones, in 2009 there were 183 headstones that could be inventoried. There were many that could only be identified by the information in the 1941 census.

…

The oldest head stone dates from 1790 and the most recent from 1986. 46 of the headstones are from the Avery family…33 of the headstones were considered to be in Excellent condition; 57 good; 51 fair; 32 poor; and 10 illegible.

Headstone with flags.

According to Lewisboro Ghosts: Strange Tales and Scary Sightings, November 15, 2007, by Maureen Koehl there is a story associated with the cemetery

…The tale unfolds on a cold winter’s night sometime after the Civil War. Along the road from Cross River to Boutonville stood the home of a poor tenant farmer whose name has long been forgotten. He was a widower with four young children. The war had not been kind to farmers in the area and this farmer struggled to keep his small family fed and clothed. Furnishings in the farmhouse were sparse. To keep warm the children often bedded down close to the hearth of the large kitchen fireplace.

On this particular evening, with a lusty wind blowing outside, the father set his children before the brightly burning hearth in his cold farmhouse, tucked them in with quilts and good night kisses and set out on the two-mile walk to one of the taverns in Cross River village – a journey he often took. The evening passed in friendly conversation with other farmers and travelers around the cheery tavern hearthside.

Meanwhile, the children slept until suddenly, a malevolent gust of wind howled down the chimney, flames licked at the quilts covering the children and in the blink of an eye the room was filled with fire and smoke.

The hours passed quickly and another round had been sent for when the tavern door burst open and a neighbor stumbled in screaming that the farmer’s house was on fire.

“My children! My children!” the farmer cried in horror as he raced from the tavern and headed in a stupor for his home. With no neighbors nearby, the sad old house burned to the ground and the children perished before the distraught dad could reach them.

Overcome with grief, the farmer searched the fire scene, but the children were not to be found. Kind neighbors buried the poor little bodies under the spreading limbs of the huge, welcoming oak tree. This tree, the Boutonville Oak, is still standing not far from the old Route 124 entrance to Ward Pound Ridge Reservation.

Residents of the reservation claim they have seen the father searching the fields and the stones of Avery Cemetery at the western end of the park for the graves of his four children. One park ranger saw the orange glow of the lantern following the road to the small cemetery. He watched as the light seemed to swing to and fro as if a man were carrying it as he walked. Once he even followed the light toward the cemetery, but as he reached the steps into the burial ground the light disappeared.

As far as we know, the distraught father has never found the graves of his children. In fact, no one has discovered the grave markers, but the tale persists and the sight of his single swinging lantern has been seen crossing the fields within the last five or ten years.

Headstones and downed trees.

Headstones and flowers