I was quite taken by these metal lion heads in Verdi Square. Pure chance! I was actually trying to get a picture with as little in the background as possible i.e. no cars, no passers-by. And, indeed, I did get such a picture. However, when I saw this one I just couldn’t resist using it.

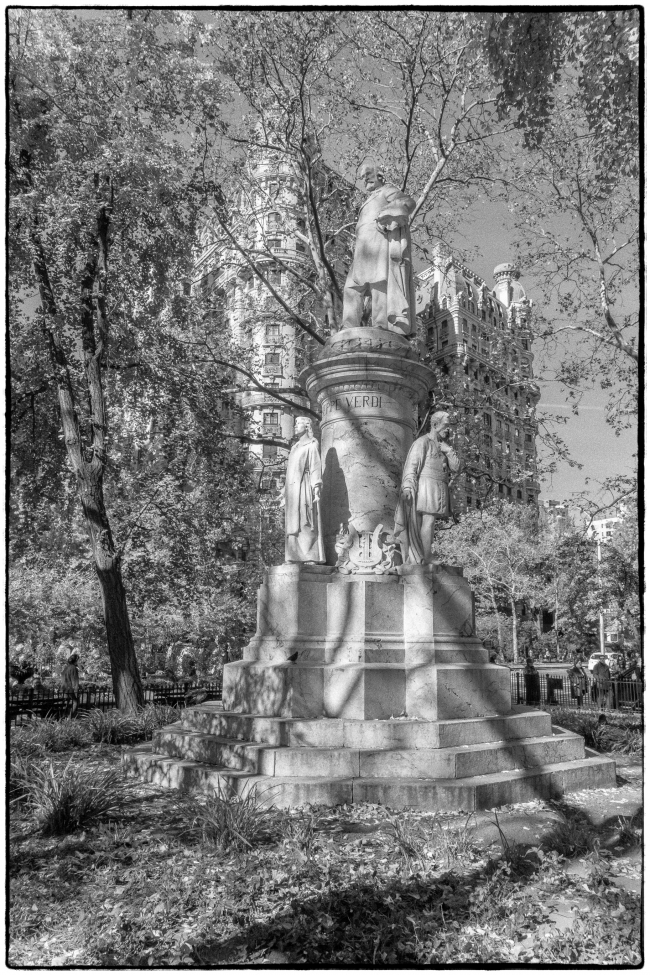

Verdi statue

This statue stands in Verdi Park on West 72nd street and Amsterdam Avenue in Manhattan. Our friend had driven us (myself, my wife, and our friend’s mother) into the city to see Spamilton. She had another stop to make and so dropped us off near the theatre. We had some time to kill and it turned out that we were right outside a Bloomingdales Outlet so the ladies went in to look around while I wandered around taking pictures.

According to the New York City Parks site:

Giuseppe Fortunino Francesco Verdi (1813–1901), one of the world’s most renowned composers, is immortalized by such operas as Aida, La Traviata, Otello, and Rigoletto, which are still performed regularly to great acclaim. This legacy is also captured in the Verdi Monument, created by Sicilian sculptor Pasquale Civiletti (1858–1952) in 1906. Made of Carrara marble and Montechiaro limestone, this statue depicts Verdi flanked by four of his most popular characters: Falstaff, Leonora of La Forza del Destino, Aida, and Otello.

…

The president of the Verdi Monument Committee, Carlo Barsotti (1850–1927), championed public recognition of pre-eminent Italians as a source of inspiration for New York’s large Italian-American community. As founder and editor of Il Progresso Italo Americano, he used his newspaper to raise funds for this project by public subscription. Barsotti was instrumental in erecting this monument as well as those honoring Christopher Columbus (1892) in Columbus Circle, Giuseppe Garibaldi (1888) in Washington Square Park, Giovanni da Verazzano (1909) and Dante Alighieri (1921) in Dante Square.

The Verdi monument was unveiled on October 12, 1906, the 414th anniversary of Columbus’s discovery of America. The day began with a march of Italian societies from Washington Square to the site at Broadway and West 72nd Street. Over 10,000 people attended the unveiling, attesting to the significance of the occasion in uniting Italian-Americans in celebration of their cultural and artistic heritage. The sculptures were unveiled by Barsotti’s grandchild who pulled a string that released a helium balloon, lifting the monument’s red, white and green shroud (the colors of the Italian flag). As it peeled away, a dozen doves – concealed in its folds – were released into the air, and flowers cascaded from the veil upon the participants.

By the 1930s the monument had suffered from the effects of weathering, pollution and vandalism, and underwent restoration, including the replacement of sculptural features. In 1974, Verdi Square was designated a Scenic Landmark by the Landmarks Preservation Commission, one of only eight public parks to receive this distinction. In 1996-97, the monument was again extensively conserved with funding from the Broadway/72nd Street Associates.

A permanent monument maintenance endowment has been established by Bertolli USA, Inc. Additional funds for landscaping designed by Lynden Miller have been donated by Harry B. Fleetwood, and the Verdi Square landscape has been endowed in memory of musician James H. Fleetwood.

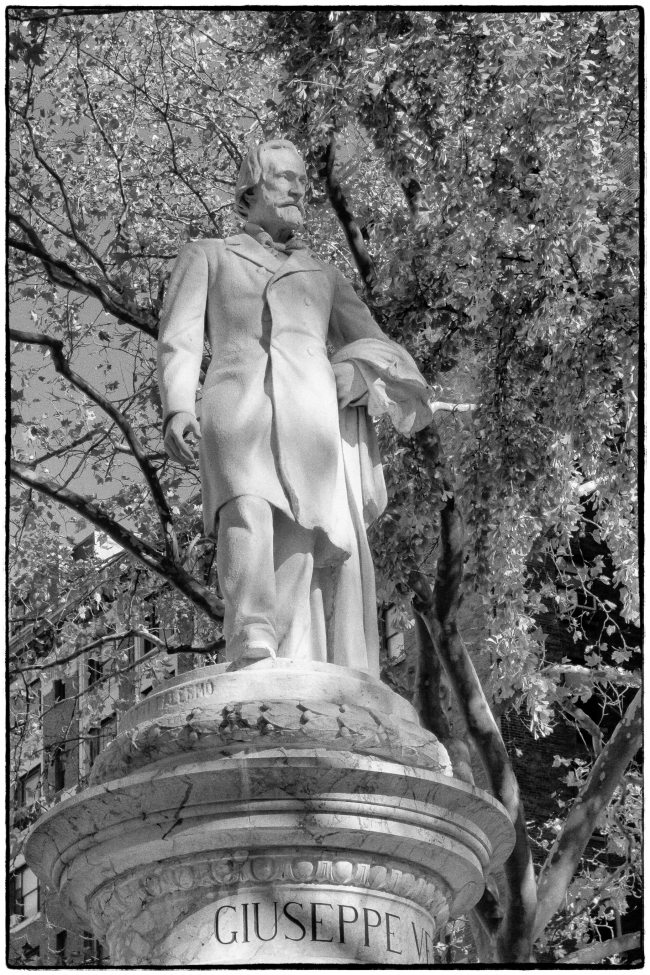

The man himself.

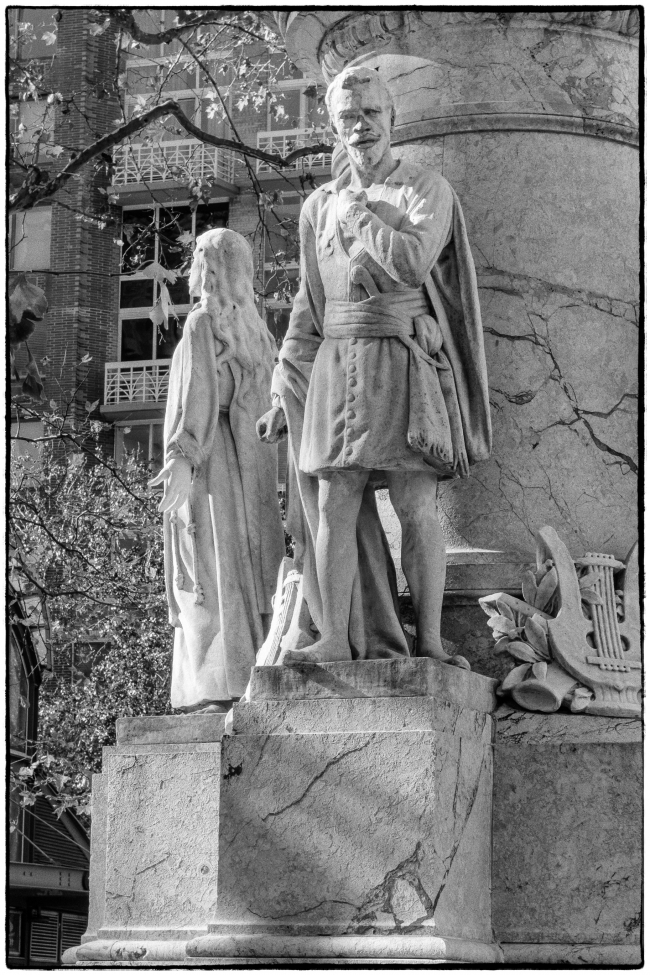

I believe the two figures are Leonora (from La Forza del Destino) and Otello (from the opera of the same name).

Community church of Yorktown cemetery – A trio of gravestones

A couple of older gravestones. They look as if they were home made rather than being professionally done. The one on the left is dated 1752 and also bears the inscription IHS and a fourth letter, which might be an ‘A’, but is hard to make out. According to Wikipedia IHS has the following meaning:

In the Latin-speaking Christianity of medieval Western Europe (and so among Catholics and many Protestants today), the most common Christogram became “IHS” or “IHC”, denoting the first three letters of the Greek name of Jesus, IHΣΟΥΣ, iota-eta-sigma, or ΙΗΣ.

The Greek letter iota is represented by I, and the eta by H, while the Greek letter sigma is either in its lunate form, represented by C, or its final form, represented by S. Because the Latin-alphabet letters I and J were not systematically distinguished until the 17th century, “JHS” and “JHC” are equivalent to “IHS” and “IHC”.

“IHS” is sometimes interpreted as meaning “Jesus Hominum (or Hierosolymae) Salvator”, (“Jesus, Saviour of men [or: of Jerusalem]” in Latin) or connected with In Hoc Signo. Such interpretations are known as backronyms. Used in Latin since the seventh century, the first use of IHS in an English document dates from the fourteenth century, in The vision of William concerning Piers Plowman. In the 15th century, Saint Bernardino of Siena popularized the use of the three letters on the background of a blazing sun to displace both popular pagan symbols and seals of political factions like the Guelphs and Ghibellines in public spaces (see Feast of the Holy Name of Jesus). The IHS monogram with the H surmounted by a cross above three nails and surrounded by a Sun is the emblem of the Jesuits, according to tradition introduced by Ignatius of Loyola in 1541. English-language interpretations of “IHS” have included “I Have Suffered” or “In His Service”, or jocularly and facetiously “Jesus H. Christ” (19th century).

Or I suppose it might just be that the person buried here had the initials IHSA.

The second gravestone has the initials D.S. and bears the date 1777.

Most of the gravestones are upright slabs so it was a bit of a surprise to see this simple cross peeping out from the dead leaves.

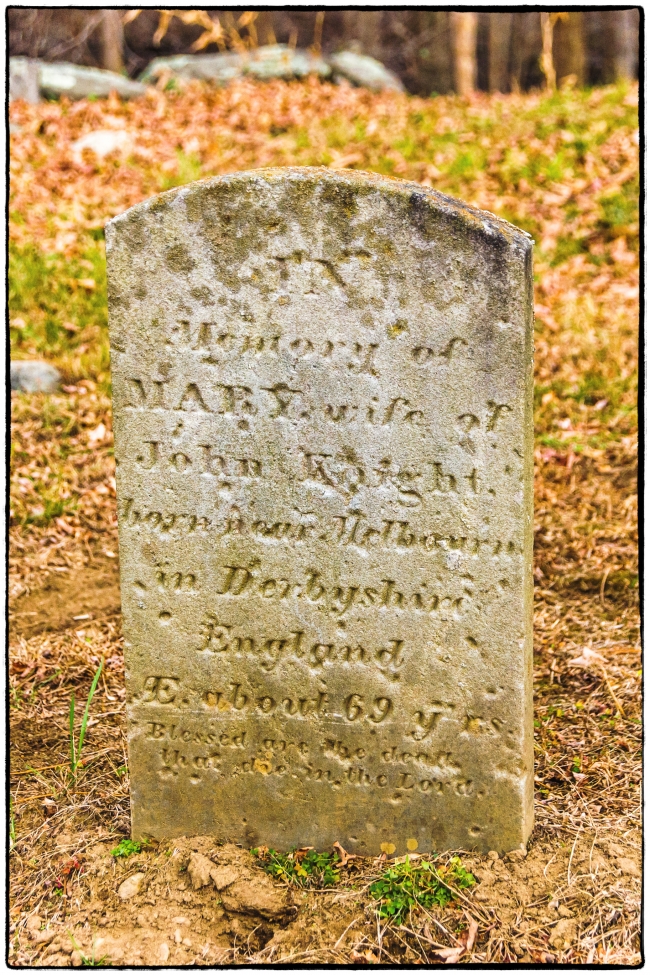

There’s nothing particularly special about this gravestone except for the inscription, which has a certain significance for me. The inscription reads: “IN Memory of Mary, wife of John Knight, born near Melbourn in Derbyshire, England (unknown symbol) about 69 years. Blessed are the dead that die in the Lord.” Melbourn is about 50 miles from where I grew up in the UK.

Community church of Yorktown cemetery – Gravestone symbols

In an earlier post I mentioned that most of the gravestones were unadorned i.e. they only had text in the form of names and inscriptions. However, I did come across a few with symbols such as the one above with a weeping willow. The Engraved: The Meanings Behind Nineteenth-Century Tombstone Symbols website gives it’s meaning as follows:

Carvings of weeping willows became very prevalent on gravestones in the early 19th century. Use of this graceful symbol reflected the young United States’ growing interest in ancient Greece. Beginning in 1762 with the publishing of The Antiquities of Athens by Stuart and Revett, which produced the first accurate surveys of ancient Greek architecture, Great Britain, Europe and eventually the United States began copying Greek style in architecture and interiors. This emulation even carried over into funerary art. For the United States, the comparison between ancient Greece and its democracy with the former colonists’ “grand new experiment” in government was inspiration for copying everything Greek.

Gravestone carvers created weeping willows alone or with Greek-inspired urns, obelisks, or monuments. The most obvious meaning of a weeping willow would seem to be the “weeping” part…for mourning or grieving for a loved one. The saying “she is in her willows” implies the mourning of a female for a lost mate. And while the Victorians took the art of mourning to new heights, the weeping willow was not just a symbol for sadness.

A native of Asia, the weeping willow is a fast growing tree that can reach fifty feet high and fifty feet wide. It tolerates most any soil and roots easily from cuttings. Because of this, they are often the first trees to appear in a disturbed site, giving them a reputation as “healers and renewers.” In many cultures, the willow is a sign of immortality, and is associated with the moon, water and femininity. The weeping willow also has connections to Greece as Orpheus, their most celebrated poet, carried willow branches with him on his journey through the Underworld. The Greek sorceress Circe planted a riverside cemetery with willow trees, dedicated to Hecate and her moon magic. It was common to place willow branches in the coffins of the dead, and then plant young saplings on their graves, with the belief that the spirit of the dead would rise up through the tree.

This one seems to combine two symbols: Ivy, which because it is evergreen is associated with immortality and fidelity and a broken bud, which is commonly found on the grave of a child or of someone who died an untimely death.

And here’s a delightful one I missed and later came across during my research:

Source: The Episcopal Cemetery Project: Eighteenth-Century Field Trip Part 3: Yorktown Baptist Church

An article (Iconography of gravestones at burying grounds) on the City of Boston website sheds some light on this winged cherub symbol:

By the 1690s, another iconographic motif began to appear on Boston’s gravestones. Called a winged cherub or a soul effigy, this motif was characterized by a fleshy face, life-like eyes, and an upwards-turned mouth. Some historians and students of material culture have asserted that the greater use of winged cherubic images, which have been interpreted as a symbol for the soul’s flight to heaven, was indicative of changing religious sentiments. This theory asserts that changing religious philosophies led to greater acceptance and more widespread usage of symbols forbidden because they were considered to be “graven images.” After much research, however, historians and statisticians have discovered that as a motif the cherub never truly displaced the death’s head. Moreover, this shift from death’s head to cherubic imagery did not correspond chronologically with any of the religious movements of the eighteenth century. Both death’s head and cherub were widely employed motifs well into the late-eighteenth century, although the death’s head appears more often on Boston stones than cherubs.

Community church of Yorktown cemetery – Statuary

As mentioned in an earlier post, there was very little statuary in this cemetery. Here are two that I spotted.

The lovely little lamb above sits on top of a grave bearing the inscription: “Little Aaron and Aramenta.”

A post (Eighteenth-Century Field Trip Part 3: Yorktown Baptist Church) on the Episcopal Cemetery site notes:

It also provides an example of how children were treated differently in the later nineteenth century as compared to the eighteenth. While before children were treated as miniature adults and accordingly were given the same gravestones as adults were, in later decades children were set apart and were commemorated with special stones. The lamb was the most popular motif for children’s gravestones.

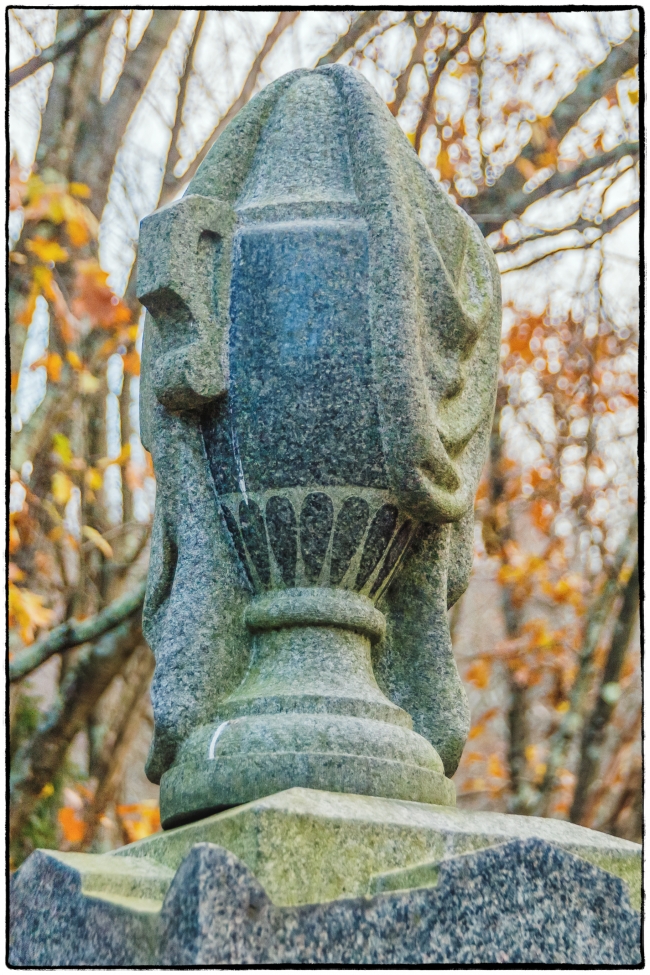

The second piece of statuary I came across was this ‘draped urn’

According to the History in Stone website:

The widely used draped urn is one of the many symbols that humans have used to represent their views towards death and the immortal spirit. The urn itself represents a classical funeral urn used for cremains. A revived interest in classical Greece led to the prevalence of the draped in urn in cemetery symbolism, even though cremation was not terribly popular at this time ( mid to late 1800s). The urn was also thought to stand for the fact that we all return to ash, or dust; the state from which God created us.

The meaning of the drape on the urn can mean many things to many people. Some feel that it symbolizes the final, impenetrable veil between the living and the dead that awaits us all. To others, it symbolizes the human shedding their mortal body and trappings to join God in Heaven. The drape can also stand for the protective nature of God over the dead and their remains, until the Resurrection occurs.