“Horace Greeley, the son of a New England farmer and day laborer, was born in Amherst, New Hampshire in February 1811. The economic struggles of his family meant that Greeley received only irregular schooling, which ended when he was fourteen. He then apprenticed to a newspaper editor in Vermont, and found employment as a printer in New York and Pennsylvania. Seeking to improve his prospects, he gathered his possessions and a small amount of money, and in 1831, set out for New York City. The twenty year old Greeley found various jobs, which provided some capital, and in 1834, he founded a weekly literary and news journal, the New Yorker.

An omnivorous reader, eager to write as well as edit, Greeley contributed to the journal. It gained an increasing audience and gave him a wide reputation. However, it failed to make money, and Greeley supplemented his income by writing, especially in support of the Whig Party. His connections with Thurlow Weed, William H. Seward, and other Whigs led, in 1840, to his editorship of the campaign weekly, the Log Cabin. The paper’s circulation rose to about 90,000, and contributed significantly both to William Henry Harrison’s victory and Greeley’s influence. Greeley also directly participated in the Whig campaign by giving speeches, sitting on committees, and helping to manage the state campaign.

In April 1841, Greeley set himself on the path to national prominence and power when he launched the New York Tribune. The Tribune was multifaceted, devoting space to politics, social reform, literary and intellectual endeavors, and news. It was very much Greeley’s personal vehicle. An egalitarian and idealist, Greeley espoused a variety of causes. He popularized the communitarian ideas of Fourier, and invested in a Fourier utopian community at Red Bank, New Jersey. He advocated the homestead principle of distributing free government land to settlers, attacked the exploitation of wage labor, denounced monopolies, and opposed capital punishment.

Assisted by a talented and versatile staff, a number of whom were identified with the Transcendentalist movement, Greeley made the Tribune an enormous success. It merged with the Log Cabin and New Yorker, expanded its staff and circulation throughout the 1840s and 1850s, and by the eve of the Civil War had a total circulation of more than a quarter of a million. This number, however, vastly understated the paper’s influence, as each copy often had more than one reader. The weekly Tribune was the preeminent journal in the rural North.

Greeley opposed slavery as morally deficient and economically regressive, and during the 1850s, he supported the movement to prevent its extension. He opposed the Mexican War, approved the Wilmot Proviso, which called for the restriction of slavery in territories gained as a result of that war, and denounced the Kansas-Nebraska Act. Greeley’s free-soil sentiments brought him quickly into the Republican Party’s camp, and he attended the national organization meeting of the party at Pittsburgh in February 1856. He supported the Republican candidate in the presidential contest of 185 6, and four years later, he attended the Republican national convention in Chicago. Initially supporting Edward Bates, he turned to Lincoln on the eve of the balloting.

The secession crisis found Greeley strongly opposed to making concessions to slavery. He denounced the Crittenden proposals, and while he argued that succession should be allowed if a majority of southerners truly wanted it, he made clear his belief t hat the rebellion was, in fact, the work of an unscrupulous minority.

Once war came, Greeley joined the radical antislavery faction of the Republican Party and demanded the early end of slavery. He denounced more conservative Republicans, like Francis and Montgomery Blair, and criticized Lincoln for proceeding too cautiously to eradicate the institution. When Lincoln finally announced his Emancipation Proclamation, Greeley applauded the decision.

During and after the Civil War, Greeley’s political course proved highly controversial. His reluctance to support Lincoln’s renomination in 1864 lost him some popular support, as did his premature efforts to bring about an armistice and peace negotiations. After the war, he joined the Congressional Radicals in supporting equality for the freedmen. The Tribune also advocated the impeachment of President Andrew Johnson. At the same time, Greeley favored measures to restore relations with the South. In 1867, he recommended Jefferson Davis’s release from prison, and he signed Davis’s bond. He gradually grew disaffected with the Grant administration because of its corruption and indifference to civil service reform, and also because of its continued enforcement of Reconstruction measures in the South.

While much admired, Greeley was also regarded as eccentric and odd, in both his personal appearance and his reformist ideas. His behavior during and after the war raised widespread doubts about his judgment. When in 1872, the anti-Grant Liberal Republicans and the Democrats nominated Greeley to challenge Grant, Greeley was attacked as a fool and a crank. So merciless was the assault that Greeley commented later that he sometimes wondered whether he was run ning for the presidency or the penitentiary. He suffered a tremendous defeat in the election, carrying only six border and southern states.

During the period following the Civil War, Greeley’s association with the Tribune underwent significant change. The era of personal editorship was ending, and as the Tribune increased in size, Greeley’s influence diminished. Following his defeat in t he election of 1872, Greeley found that control of the paper had passed out of his hands. Shocked by his electoral repudiation, the recent death of his wife, and the effective loss of his editorship, Greeley suffered a breakdown of both mind and body, and died on November 29, 1872.”

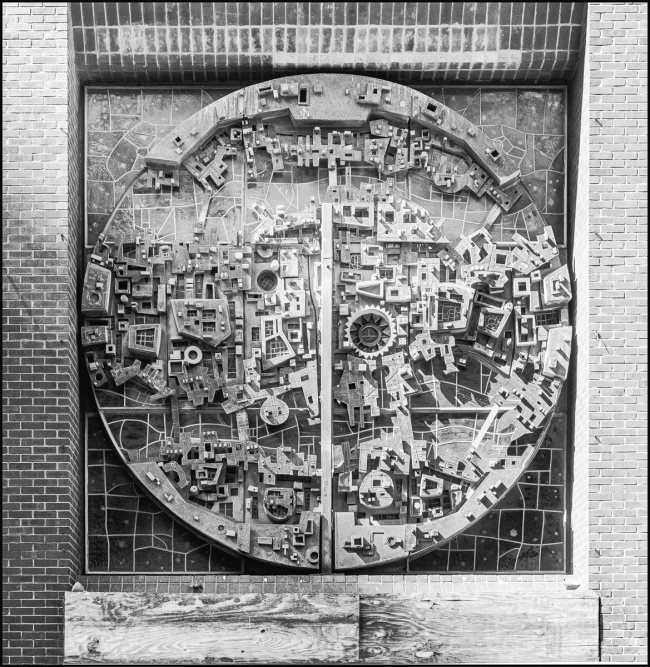

The outdoor bronze sculpture of Horace Greeley by Alexander Doyle stands in Greeley Square Park, New York City. It was cast in 1892, dedicated on May 30, 1894 and sits atop a Quincy granite pedestal. It contains the following inscription:

“The Greeley House is located at King (New York State Route 120) and Senter streets in downtown Chappaqua, New York, United States. It was built about 1820 and served as the home of newspaper editor and later presidential candidate Horace Greeley from 1864 to his death in 1872. In 1979 it was listed on the National Register of Historic Places along with several other properties nearby related to Greeley and his family.

Built in the 1820s as a typical small farmhouse, it was expanded in the mid-19th century. Greeley, editor of the New-York Tribune, settled in Chappaqua shortly before the Civil War in the mid-19th century, living there with his family primarily during the summer. After a mob of citizens opposed to Greeley’s abolitionist editorial stance threatened his wife at their earlier “House in the Woods,” Greeley bought the farmhouse and moved his family there, near the hundred acres (40 ha) where he ran a small farm and practiced experimental agricultural techniques.

After the war, Greeley built a mansion called “Hillside House” to live in, but died along with his wife shortly after the 1872 presidential election, where he ran on the Liberal Republican line against incumbent Ulysses S. Grant, so his children lived there instead, pioneering the suburban lifestyle that was later to define Chappaqua and its neighboring communities. Both of Greeley’s other houses burned down later in the 19th century, leaving the Greeley House the only one extant.

It, too, was almost demolished after falling into serious neglect in the early 20th century. After its restoration in 1940, it was used as a restaurant and gift shop. Following another restoration effort in the early 21st century, it is now the offices of the New Castle Historical Society.” (The Greeley House)