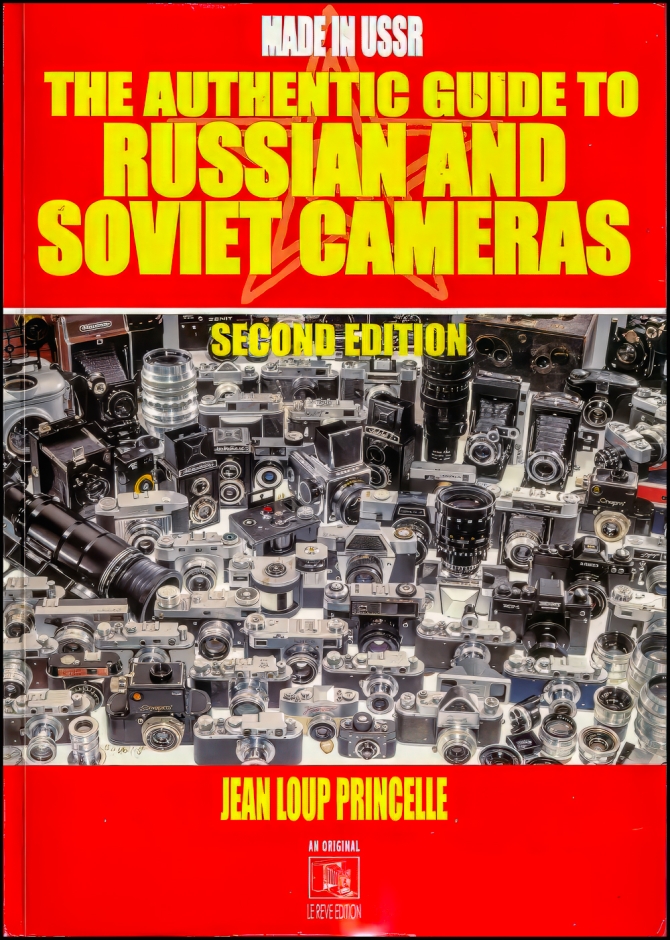

My late wife started my interest in photography around 1980 when she gave me my first serious camera: a Minolta Hi-Matic 7sII, a compact rangefinder camera. So, when I started to collect cameras around 2011, I thought I would concentrate on other compact rangefinder cameras (famous last words). Not long afterwards I decided that I would take a look at full-size rangefinder cameras. Of course, when you think about full-size rangefinder cameras the first name that comes to mind is Leica. I soon figured out that Leica cameras were expensive, and since I wasn’t sure how long this camera collecting hobby would last (so far, it’s lasted 14 years) I decided to stay away from Leicas (also famous last words). However, I quickly learned that copies of Leicas were available and that those from the former Soviet Union (FSU) were quite inexpensive. So, I bought a couple. The person that I bought them from suggested the if I was seriously going to collect FSU cameras, I should get a copy of this book by Jean Loup Princelle, which probably not coincidentally he was also selling. His wise words seemed to make sense, so I bought a copy. I found it fascinating, but I wasn’t all that much into camera collecting yet, so I put it aside. Unfortunately, as luck would have it, we had a major water leak (flood would perhaps be a better word) and the book was destroyed, and I never got around to replacing it.

Fast forward to a few weeks ago. I was browsing around on eBay and I came across a copy at a very reasonable price. The book is quite expensive normally (it’s been out of print for some time and can be difficult to find) and I snapped it up.

When it arrived, I realized what a gem it is. If you ever wanted to know the exact difference between a FED 1a and a FED 1b (or even for that matter where the name FED comes from) this book is for you. It’s almost 300 pages long and has extensive listings of every FSU camera and lens ever made. There are also short essays on every camera manufacturer as well as a nine-page history of Russia and FSU. There are also a couple of short timelines outlining the history of FSU cameras. Scattered throughout the book are essays such as “Photography in Russia in the 19th century; “From Pre-Industrial Cameras to the Cameras of the 60’s to the 90’s”; and “Subminiatures, Military Cameras and Other Quite Special Cameras”.

It really is a very impressive achievement. And how can you not love camera manufacturers with names like Fag, Zorki, Gomz, and Voomp?

I mentioned above that I initially bought two FSU rangefinder cameras (copies of the Leica II – or D as they tend to be referred to in Europe). In case anyone is interested they were (or rather are as I still have them) a FED 2 type-e (I didn’t know it was a type-e until I just looked it up) and a ZORKI 4 variant with the name in Roman instead of Cyrillic letters.

FED 2 type-e

ZORKI 4 variant with the name in Roman instead of Cyrillic letters

They both use Leica Thread Mount (LTM or M39) lenses: a 50 mm f/3.5 collapsible FED 10 lens. It’s said to be a copy of the 5cm f3.5 Leitz Elmar. However, I’ve read that although it looks like an Elmar, its design is actually closer to that of a Zeiss Tessar 50 mm f/3.5 (the Leitz Elmar has the aperture located behind the first element, the Zeiss Tessar has it behind the second element). The FED-10 was manufactured from 1934–1946(?) This one has the old-style aperture scale f/3.5, 4.5, 6.3, 9, 12.5, 18 and a 50 M/M indicating that it was built before World War II. Post war lenses feature the new-style aperture scale f/3.5, 5.6, 8, 11, 16 and a 50 MM engraving.