The New York Public Library has come up with an interesting new tool:

Photographers’ Identities Catalog (PIC) is an experimental interface to a collection of biographical data describing photographers, studios, manufacturers, and others involved in the production of photographic images. Consisting of names, nationalities, dates, locations and more, PIC is a vast and growing resource for the historian, student, genealogist, or any lover of photography’s history. The information has been culled from trusted biographical dictionaries, catalogs and databases, and from extensive original research by NYPL Photography Collection staff.

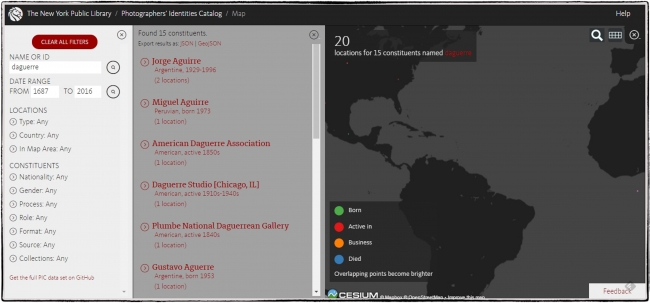

The interface allows you to filter according to a number a criteria: Name or ID; Date Range (year); Location (Type e.g. birth; Country or Geographical Area; In Map Area); Nationality; Gender; Process (e.g. Autochrome); Role (e.g. Collector or Dealer); Format (e.g. Panoramic Photographs); Source; Collections.

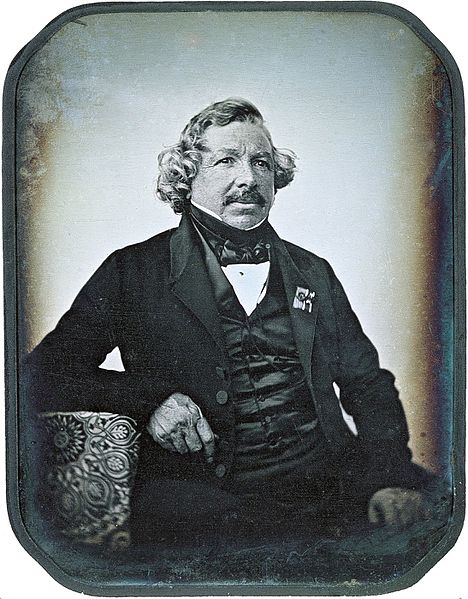

Once you’ve applied your filters you then get a list of results (since the system uses a “fuzzy search” algorithm you usually get more than you really want. For example, setting the name filter to ‘Daguerre’ produces ‘Aguirre’, ‘Aguerre’, and Ministere de la Guerre’ as well. The ‘Daguerre’ I was looking for was 9th in the list.

I’m a fan of Joseph Sudek so I thought I’d see if I could find him with some general criteria and not using his name. I imagined that I only knew that he was male; from somewhere in Eastern Europe; and was known for panoramic photographs (among other things). So I set up the filters: Gender – Male; Country – There was no Eastern Europe so I had to select Europe instead; Format – Panoramic Photographs. Unfortunately my attempt was not successful. His name did not appear on the results list.

The map takes up a lot of screen space and I’m not entirely sure how useful it is. This may well be because of my ignorance of how it’s supposed to work however.

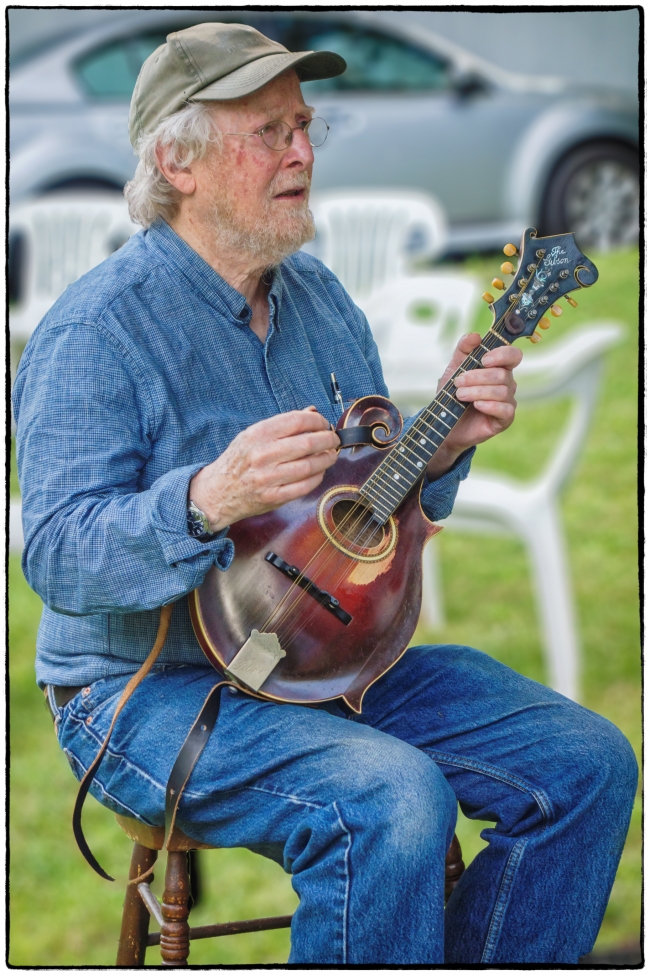

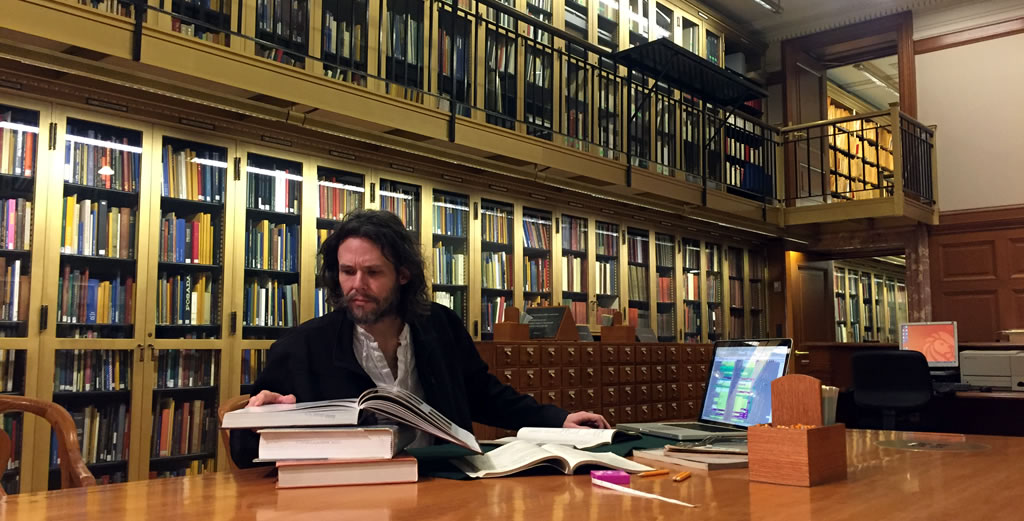

David Lowe, Photography Specialist at the New York Public Library, and the primary editor of PIC, in the Photography Room.

So many thanks to the New York Public Library for such a useful tool. Over time I’m sure it will become even more useful in terms of additional content and system improvements. One of the FAQs is: “I have information PIC lacks, or I’ve spotted an error. How do I contribute or request a correction?” The answer is “Please let us know! Use the feedback link in the bottom right of the map. It is helpful if you include the Record ID number to identify the photographer in question. That ID can be found after the Name, Nationality and Dates of the constituent.”