A few days before Christmas my wife was going to lunch with a friend in Pleasantville, NY. I needed to get out of the house so I decided to go along with her. I knew that there was a small bookstore in Pleasantville and I thought that I would “check it out” and then grab a bite to eat.

I set off walking in the direction of the bookstore when I spotted this photo store: Photoworks. I’d noticed it before, but it always seemed to be closed when I went by. Assuming that it was largely devoted to photofinishing, scanning etc. I was about to walk by when, looking through the window, I noticed a glass case inside – full of vintage cameras. I went in and asked the women if the cameras were for sale or just for display. She called her husband, George who emerged from the back somewhere and we had a long conversation about vintage cameras. Inside the case were two Nikon Fs (see above). I’d wanted one of these for a while, the price was right and the prospect of actually having a human being I could bring the camera back to in case of problems was appealing. I told him I would consult with my wife and return later.

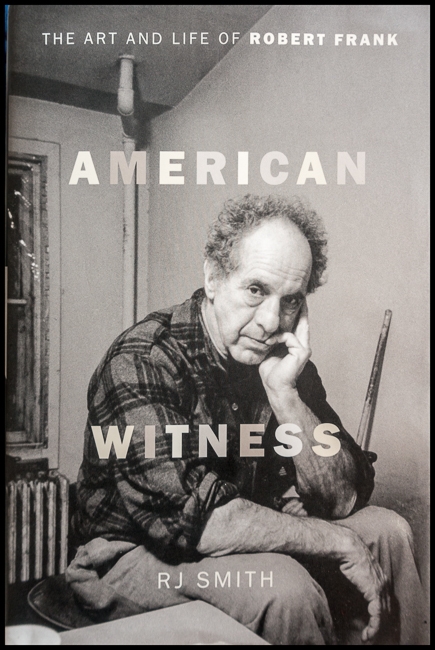

I continued on to the bookstore: The Village Bookstore, a very pleasant establishment, small but well stocked and with a nice atmosphere. Among the shelves I came across (and purchased) this recently published biography of Robert Frank: American Witness. The Art and Life of Robert Frank.

Time to start looking for somewhere to eat. Then I spotted this building. On the front it said “The Gordon Parks Foundation“, so I went inside to take a look. I didn’t even realize that such an institution existed in Pleasantville. Inside they had a small selection of books by/on Gordon Parks but the bulk of the space was taken up by an exhibition: Element: Gordon Parks and Kendric Lamar. According to the Foundation’s website:

The Gordon Parks Foundation announced the opening of ELEMENT – a new exhibition on view at the Foundation’s exhibition space from December 1—February 10 showcasing Gordon Parks photographs that inspired rapper Kendrick Lamar’s music video ELEMENT from his album, DAMN. Lamar, known for using powerful images in his music videos, directly references and revives a number of Parks’ images that explore the lives of Black Americans, including the 1963 photo Boy With Junebug, Untitled, the 1956 photo from Parks’ “Segregation Stories” series, Ethel Sharrieff, a 1963 photo from his “The White Man’s Day Is Almost Over” photo essay about Black Muslims, as well as photos form Parks’ 1948 “Harlem Gang Leader” series.

“Gordon Parks’ work is continuing to have a great impact on young people – and particularly on artists like Kendrick who, use the power of imagery to examine issues related to social justice and race in our country,” said Peter W. Kunhardt, Jr., Executive Director of The Gordon Parks Foundation. “With ELEMENT the music video, Kendrick has helped to call attention to one of the most important artists of our time.”

Long-time friend and supporter of The Gordon Parks Foundation, Kasseem Dean (aka, Swizz Beatz) noted, “I’m so inspired that my friend Kendrick Lamar chose the iconic imagery of the legendary Gordon Parks in his video for ELEMENT. It’s a prime example of how contemporary change makers – artists, musicians, filmmakers, designers – can borrow from the greats of the past who were also working towards social change.”

At the foundation of ELEMENT. are Parks’ photo essays exploring issues related to poverty and social justice which established him as one of the most significant story tellers of American society. “Harlem Gang Leader,” the photo essay published in LIFE magazine, is credited with introducing Parks to America. The photos explored the world of Leonard “Red” Jackson, the leader of a gang in Harlem. Soon after, Parks was offered a position as staff photographer for the magazine, making him the first, and for a long time the only, African American photographer at the magazine. Also published in LIFE, Parks documented the daily life of an extended African American family living under Jim Crow segregation in the rural South entitled “The Restraints: Open and Hidden.”

The Guardian has also published an interesting article on this exhibition: The story behind Kendrick Lamar’s Gordon Parks exhibition

After that I decided that I didn’t have enough time to eat before meeting my wife so I adjourned to a nearby bar

Foley’s Club Lounge for a couple of beers.

According to Mount Pleasant by George Waterbury, Claudine Waterbury, Bert Ruiz:

Harry Foley was a Pleasantville High School Basketball legend. He was also a Niagara University Hall of Fame and Westchester County Hall of Fame athlete. He bought Gorman’s Club Lounge on Bedford Road in 1950 and maintained the establishment until the 1970s. Foley’s Club Lounge has been a traditional watering hole for generations of Pace University students for nearly a half century.

When my wife finished her lunch we met up and I asked her if she’d like to buy me a Christmas present. She said yes so it was off back to the photo store to pick up the Nikon F with Photomic Ftn finder.

All in all a photographically speaking an interesting day, if rather unexpected.