Although we didn’t plan it that way we ended up spending most of the time at the Surrealism Beyond Borders Exhibition. For those who might be interested the exhibition runs until January 30. Above: Armoire surréaliste (Surrealist Wardrobe), 1941. Marcel Jean.

Landru in the Hotel, Paris (Landru en el hotel, Paris), 1932. Antonio Berni.

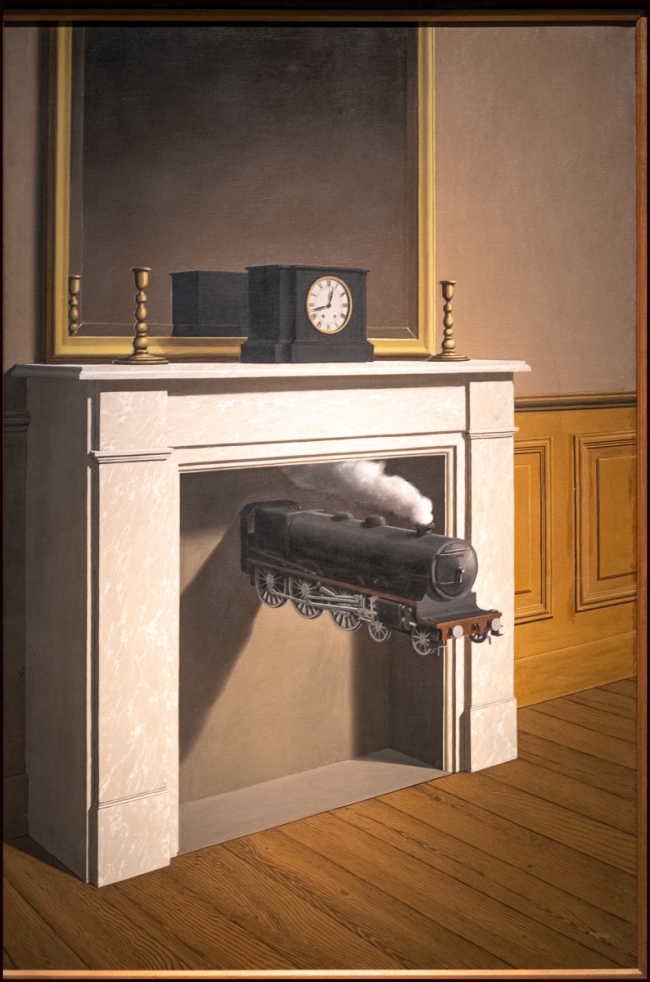

An onlooker considers one of my personal favorites: La durée poignardée (Time Transfixed), 1938. René Magritte

La durée poignardée (Time Transfixed) again. This time with no obstructions.

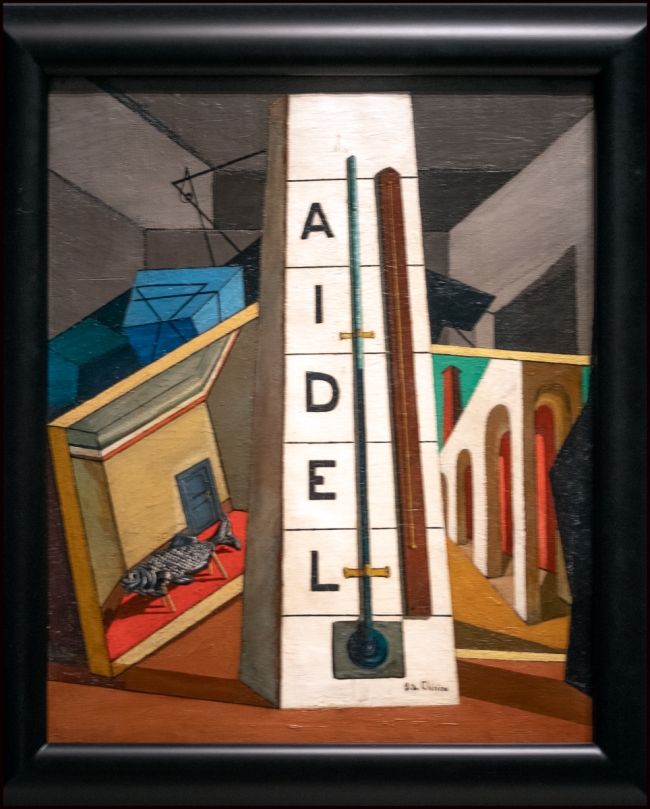

Le rêve de Tobie (The Dream of Tobias), 1917.Giorgio de Chirico

Nus (Nudes), 1945. Samir Rafi.

Pas de deux (Amanecer) (Pas de Deux [Dawn]), 1953. Luis Maisonet Crespo.

Towards the Tower (Hacia la Torre), 1960. Remedios Varo.

Viewers studying Construction molle avec des haricots bouillis (Premonition de la guerre civile) (Soft Construction with Boiled Bean [Premonition of Civil War]), 1936. Salvador Dalí

Construction molle avec des haricots bouillis (Premonition de la guerre civile) (Soft Construction with Boiled Bean [Premonition of Civil War]) again.

Finial from a Slit Gong (Atingting Kon), early to mid-20th century. Ambrym Island

Taken with a Fuji X-E3 and Fuji XF 35mm f1.4 R