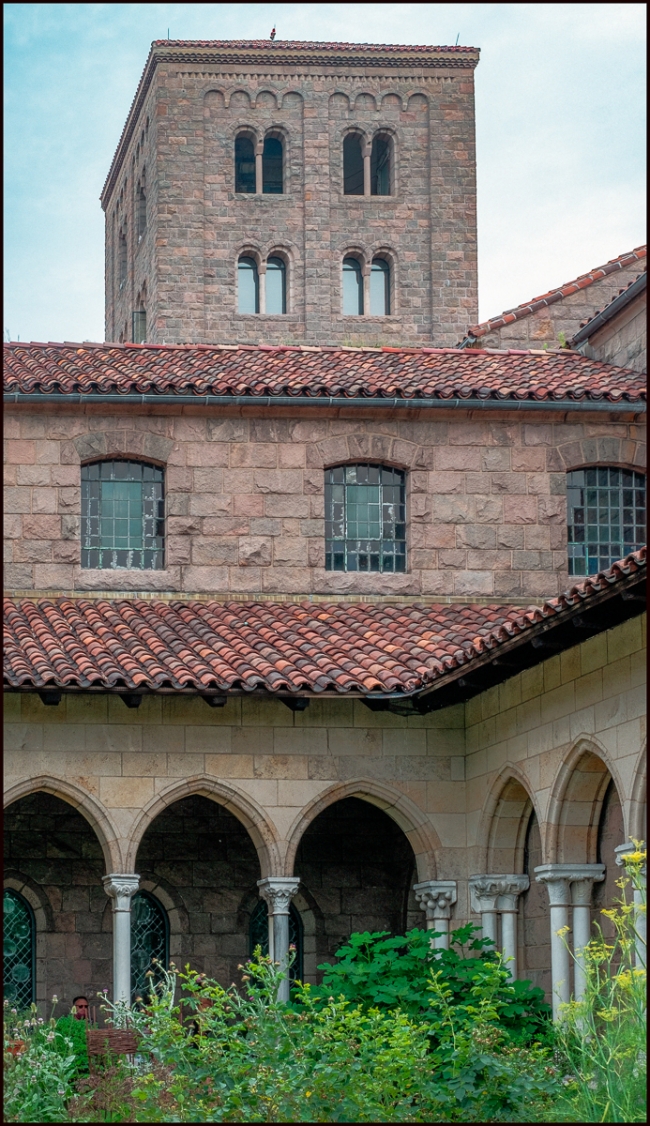

“The building is set into a steep hill, and thus the rooms and halls are divided between an upper entrance and a ground-floor level. The enclosing exterior building is mostly modern, and is influenced by and contains elements from the 13th-century church at Saint-Geraud at Monsempron, France, from which the northeast end of the building borrows especially. It was mostly designed by the architect Charles Collens, who took influence from works in Barnard’s collection. Rockefeller closely managed both the building’s design and construction, which sometimes frustrated the architects and builders.

The building contains architecture elements and settings taken mostly from four French abbeys, which between 1934 and 1939 were transported, reconstructed, and integrated with new buildings in a project overseen by Collins. He told Rockefeller that the new building “should present a well-studied outline done in the very simplest form of stonework growing naturally out of the rocky hill-top. After looking through the books in the Boston Athenaeum … we found a building at Monsempron in Southern France of a type which would lend itself in a very satisfactory manner to such a treatment.”

The architects sought to both memorialize the north hill’s role in the American Revolution and to provide a sweeping view over the Hudson River. Construction of the exterior began in 1935. The stonework, primarily of limestone and granite from several European sources, includes four Gothic windows from the refectory at Sens and nine arcades. The dome of the Fuentidueña Chapel was especially difficult to fit into the planned area. The east elevation, mostly of limestone, contains nine arcades from the Benedictine priory at Froville and four flamboyant French Gothic windows from the Dominican monastery at Sens.” (Wikipedia).

Taken with a Fuji X-E1 and Fuji XC 16-50mm f3.5-5.6 OSS II