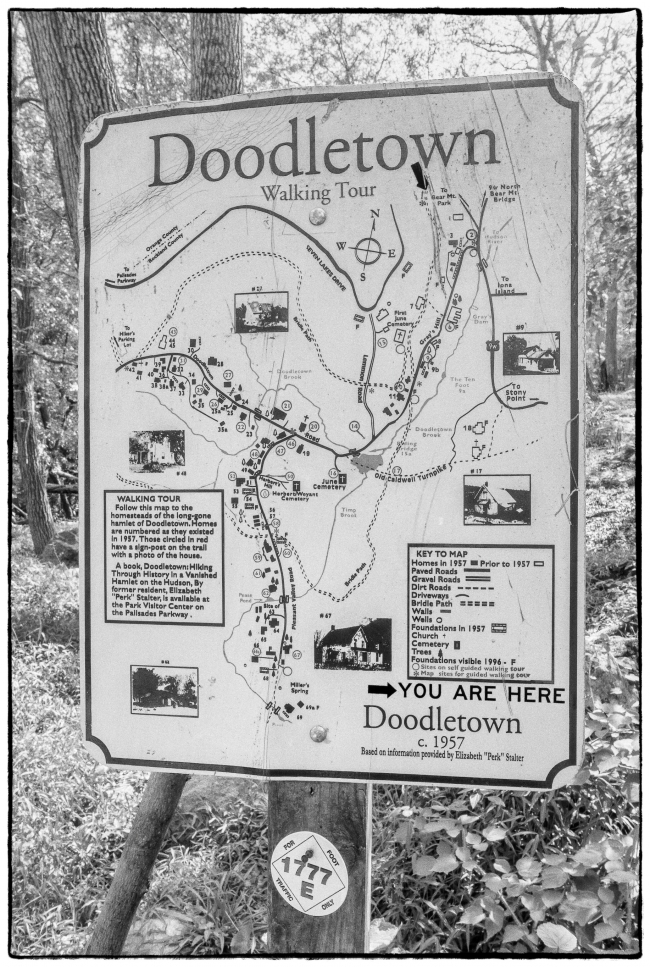

I’ve always found Doodletown to be a fascinating place. Even the name is, to me, charming.

According to a site devoted to Doodletown (unfortunately I originally gave the wrong url, and now almost 6 years later I can no longer remember what it was):

Doodletown has been lived in continuously since at least 4-10-1762, and possibly before, when Ithiel June purchased 72 acres, and settled the picturesque valley. There are several theories as to how Doodletown got its name. One is that the words “dodo del” mean dead valley, perhaps because of fire damage, or of dark shadows. Another is that logging in 1700’s was called “doodling”. Doodletown had extensive logging, hence the reference. Another more romantic notion states that during the Revolutionary War, the British troops that marched through the hamlet on their way to attack Forts Clinton and Montgomery in 1777, played Yankee Doodle Dandy to antagonize the residents. The former is probably correct as maps of the time already indicated that Doodletown existed. An historic event occurred during that march. Patriot scouts encountered the British and there was a brief skirmish in Doodletown.

Beginning

Early life for the townsfolk was hard, yet they prospered. They found employment logging, mining, ice harvesting, at Iona Island, West Point, and later, the Interstate Park. Some had small farms. The first church, which was also used as a school, was built in 1851. A second church and a second school were built in the late 1880’s. Slowly, the town grew.

Early Life

In its peak in the 1920’s, Doodletown had a new, larger school, the finest building in the town. There were three primary roads, a lane connecting to Seven Lakes Drive, several dead end lanes, two working cemeteries, and approximately seventy homes. Many families like the Junes, Herberts and Weyants had lived there for generations.

Beginning ca 1917, and throughout the following decades, the Park began to expand its borders by slowly purchasing the settlements properties. Many of these properties were then rented out to Park employees. In 1962, the Park planned to build a ski resort where Doodletown was located. The residents were to be bought out. Some were relieved to be able to sell. At the time, homeowners were unable to secure home improvement loans, and buyers were unable to obtain mortgages, since the lenders felt that the town’s demise was inevitable. Others, strongly resisted, and were threatened with condemnation through eminent domain. In early 1965, the last of the Doodletown residents had moved out. This included the June family, whose members had lived there continuously since 1762. Ironically, the ski resort was never built. The Park now owned all of the land, except for the two cemeteries. In 1966, the buildings were demolished and the debris was buried. The town was left to revert to its natural state, wild and largely overgrown.

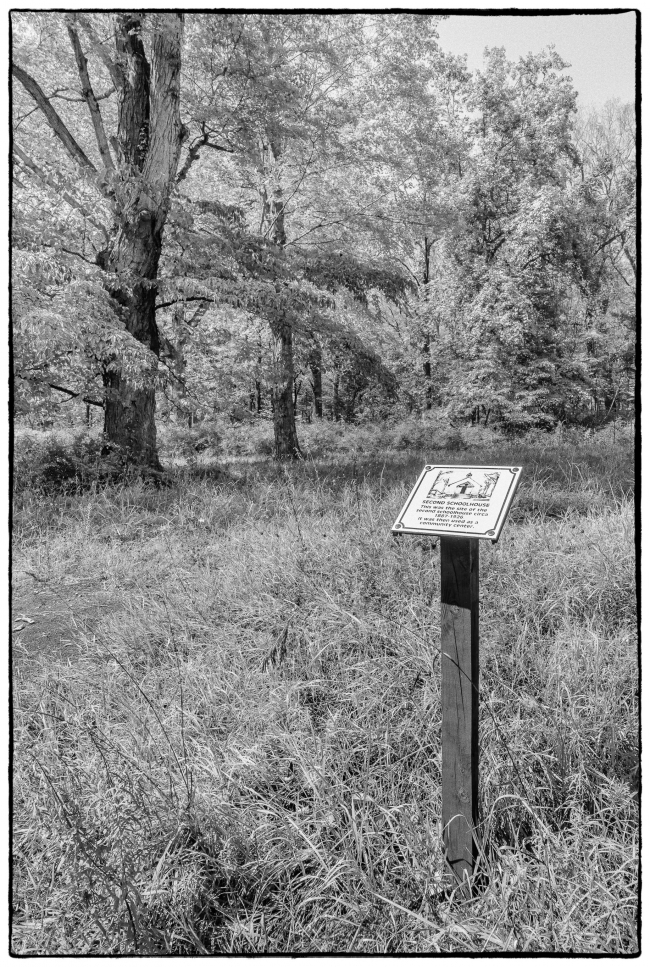

Unfortunately there’s not much left. Some of the locations, such as the one above, have markers. However, over time many of the markers have fallen apart and/or been destroyed by vandals. This particular marker reads: “Second Schoolhouse. This was the site of the second schoolhouse circa 1887-1926. It was then used as a community center.”

A stairway to nowhere. According to its marker: “Horace Herbert Home. These steps lead to the Horace Herbert Home, Build Circa 1900. It had an open porch with commanding views. Note the large well cover just across the street and a few steps up the road, was Horace’s garage.”

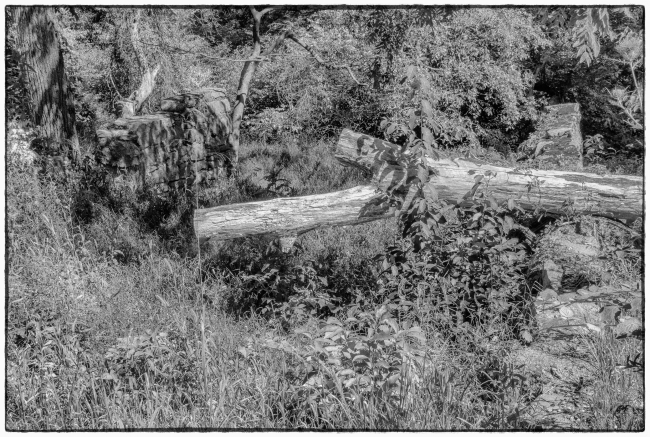

According to its marker: “Gray’s Barn. These barn walls are one of the best examples of Doodletown’s remains. It was part of the Gray family property, and is suggested (sic) a Mr. Green lived here ca. 1920. He grew corn and strawberries on the hillside. It was later used by William Herbert, whose home was adjacent up the hill. The dead end lane behind the barn lead to William’s blacksmith shop.”

Taken with a Sony RX100 M3.