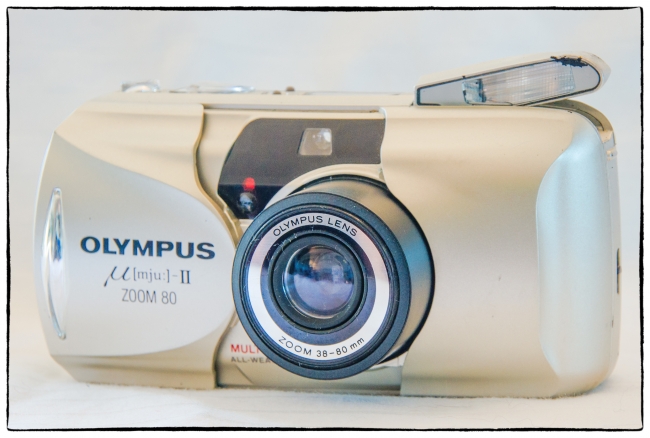

Unlike the Mju (Infinity) and Mju II (Infinity Stylus Epic), which both have fixed 35mm lenses (at f3.5 and f2.8 respectively) this one has a 38-80mm, f/4.5-8.9 zoom (5 elements in 4 groups) focusing to two feet and with apertures from f/4.5-8.9. I bought it at a nearby Goodwill store for the astronomical price of $1.99 in great cosmetic condition.

There’s not really a lot you can say about this camera. It’s a pretty standard Olympus camera of the period with a sleek, still fairly modern (it was manufactured from 1999-2003) look. It’s small and fits easily into a pocket and has the standard sliding door design. Slide the door to the right and with a whir the lens extends and a flash pops out.

The camera top has rocker switch which allows you to zoom the lens. When you do the lens extends about an inch more bringing its total length to about two inches. Right next to the zoom switch is the fairly large shutter release, and to the left of that a couple of small buttons, one of which controls the self timer and remote, and the other the flash (on, redeye reduction, off). This latter button also allows you to set an infinity mode and a night scene mode. Between these two buttons and the flash sits a small LCD, which shows which frame you’re on (or ‘E’ of if no film is in the camera) and also displays the various icons indicating which options (flash, self timer etc.) you’ve chosen. I have the quartz date version so the LCD also displays the date and time.

Just behind, and a little lower than the LCD is a viewfinder and two small buttons (mode and set) for setting the quartz date options. The viewfinder has no framelines, but it does have marks for parallax concentration. It’s fairly bright and clear and displays a central cross.

When you half-press the shutter release one or both of to LEDs light up. A green LED indicates that focus has been achieved, and an orange one warns of a slow shutter speed (suggesting that flash should be used or the camera stabilized).

The rear door has a small window to show you what film is in the camera. Film loading is easy: pull up on a small tab on the left side of the camera and the back opens; put in the film; extend the leader and then close the door. The film then advances to the first frame and a number ‘1’ appears in the LCD on top. ISO (50-3200) is set automatically based on DX code (if the film is not DX coded a default of 100 is set). After the shutter release has been pressed the film advances automatically and when you reach the end of a roll rewinds automatically

There’s a tripod socket on the right side of the base, a film plane indicator to the left and right next to it a tiny button for rewinding the film mid-roll. On the right side of the body a door to the battery compartment opens to allow you to insert a single CR123 battery. Some models have a panorama switch, but apparently mine doesn’t. That’s OK as I wouldn’t have used it anyway. The camera claims to be weather proof.

That’s really about it.

Using it was easy and everything appeared to work as anticipated (of course I won’t really know until I get the film back). The viewfinder was, in my opinion, better than that of last month’s Mju I. Even with my glasses on I could see the entire frame and both LEDs. I have the usual complaint (common to all Olympus Infinity models I think) that when you turn on the camera it defaults to having the flash on. So if you don’t want it on (which I don’t almost all of the time) you have to remember to turn it off. I also have my usual quibble about all point and shoot cameras i.e. that it bothers me that I don’t know what aperture/shutter speed the camera is selecting.

I’ve read that there’s a more serious problem with this camera. Apparently over time the light baffles around the lens deteriorate and let light in. This seems to be a common problem, but of course I won’t know if mine suffers from it until after the film has been developed. Apparently there’s no easy solution for this problem.

Jim Grey has an interesting review of this camera on Down the Road. In his initial paragraph he writes:

I wonder if the Olympus Stylus Epic Zoom 80 ever really had a chance, given that it was introduced in 1999. Within a few years everybody who bought auto-everything 35 mm cameras like these would be ditching them for digital cameras. If the number of these cameras available on eBay at any moment is an indication, Olympus sold a ton of these cameras. That they all seem to be in like-new condition says a lot about their unfortunate place on photography’s timeline. This camera’s time in the sun was so short that many of them show up on eBay with marketing stickers still on their faces.