After visiting Fort Montgomery we decided to have lunch and then afterwards follow the trail over Popolopen Creek up to what’s left(virtually nothing) of Fort Clinton. However, we changed our plans and decided to visit the nearby Stony Point battle site, described on its website as follows:

…Battle of Stony Point, one of the last Revolutionary War battles in the northeastern colonies. This is where Brigadier General Anthony Wayne led his corps of Continental Light Infantry in a daring midnight attack on the British, seizing the site’s fortifications and taking the soldiers and camp followers at the British garrison as prisoners on July 16, 1779.

By May 1779 the war had been raging for four years and both sides were eager for a conclusion. Sir Henry Clinton, Commander-In-Chief of the British forces in America, attempted to coerce General George Washington into one decisive battle to control the Hudson River. As part of his strategy, Clinton fortified Stony Point. Washington devised a plan for Wayne to lead an attack on the garrison. Armed with bayonets only, the infantry captured the fort in short order, ending British control of the river.

The Stony Point Lighthouse, built in 1826, is the oldest lighthouse on the Hudson River. De-commissioned in 1925, it now stands as a historical reminder of the importance of lighthouses to commerce on the Hudson River. The opening of the Erie Canal in 1825 unleashed a surge of commercial navigation along the Hudson River, by linking New York city to America’s heartland. Within a year, the first of the Hudson’s fourteen lights shone at Stony Point and others soon followed, designed to safely guide maritime travel along the river. Many light keepers, including several remarkable women such as Nancy and Melinda Rose at Stony Point, made their homes in the lighthouse complexes, and ensured that these important navigational signals never failed to shine.

The site features a museum, which offers exhibits on the battle and the Stony Point Lighthouse, as well as interpretive programs, such as reenactments highlighting 18th century military life, cannon and musket firings, cooking demonstrations, and children’s activities and blacksmith demonstrations.

Cannon overlooking the Hudson River. I believe they fire it on weekends.

Stony Point Lighthouse.

Another view of the lighthouse giving only a hint of the spectacular view down and across the River Hudson.

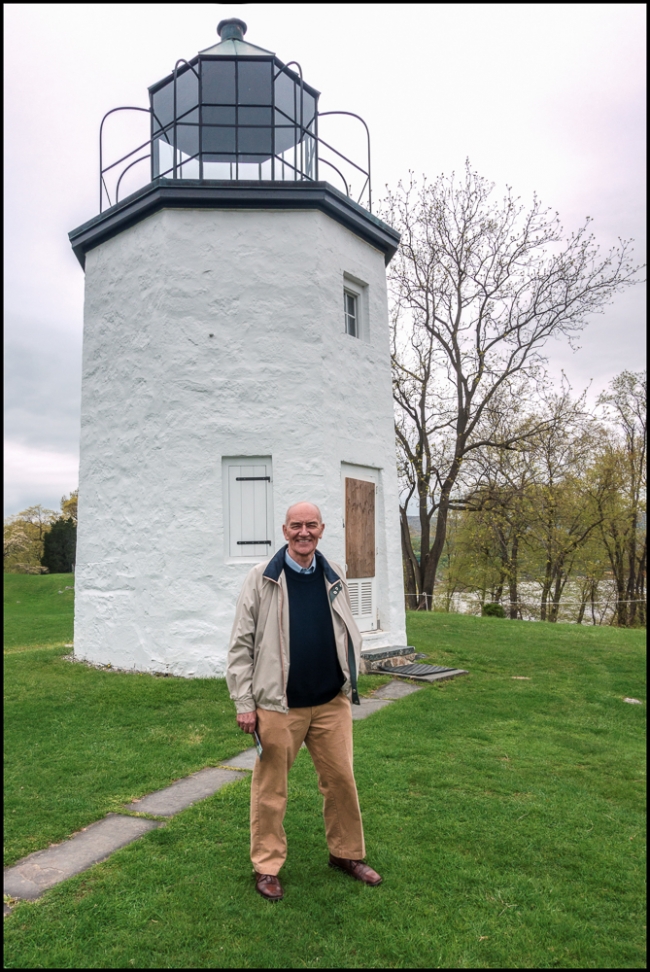

Ken by the Lighthouse.

I reclaim Stony Point for the British Empire.

Taken with a Sony RX-100 M3.