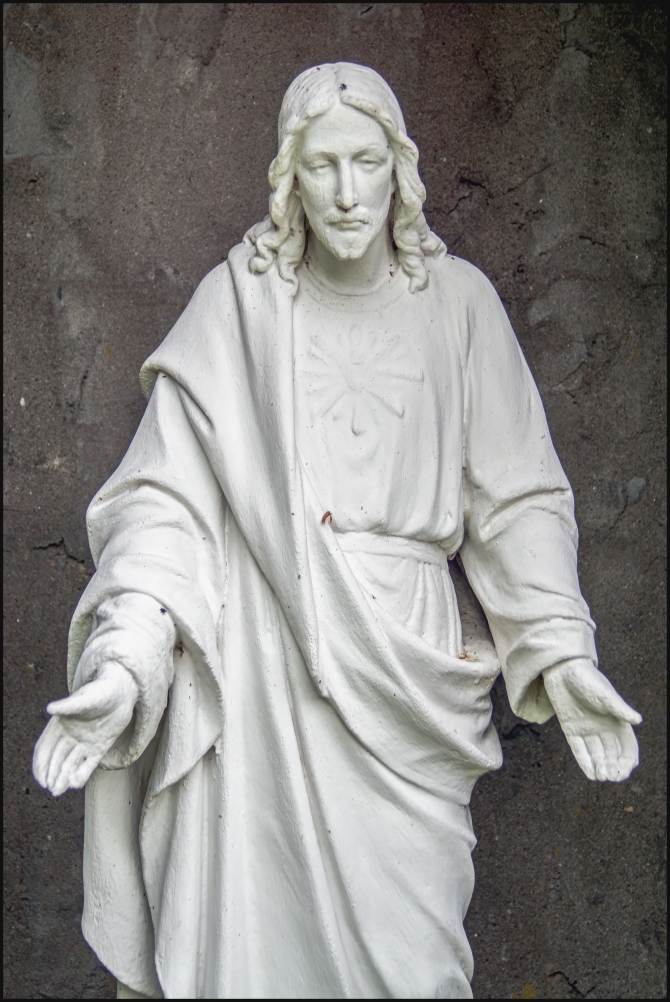

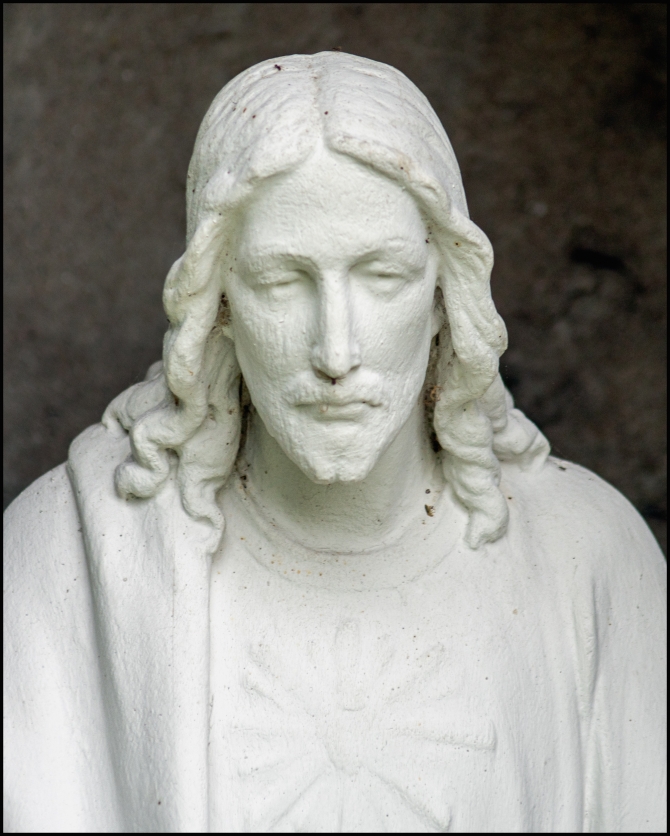

At Mariandale.

“Situated on 61 wooded acres, The Center at Mariandale is a spiritual retreat center founded on the mission of the Dominican Sisters of Hope, with care of the Earth as its central tenet. The retreat center offers programs and events centered around spirituality and love for Nature and the Earth. They encourage our community and retreatants to find ways to lighten our footprint on the Earth, and to practice land and environmental justice.

It sponsors retreats and programs in numerous areas, including spirituality, contemplative practices, social and environmental justice, interfaith dialogue, the arts, wellness of body, mind, and spirit, and more.

The center also welcomes nonprofit groups and organizations for day or overnight workshops, retreats, and conferences. Our guests enjoy the quiet, serene environment at the center.”

When I first started collecting old film cameras, this was one of the first places I visited to try them out. At that time there were some lovely, old barn-like buildings on the property. There were also a few interesting old, rusting farm implements. Unfortunately, they have now gone. For a couple of pictures taken at the time take a look at the bottom of this post.

Taken with Sony A77II and Minolta 35-105 f3.5-4.5 except for the last two, which were taken with a a Krasnogorsk Mechanical Factory (KMZ), Zorki 4 and KMZ 50mm f2 Jupiter 8.