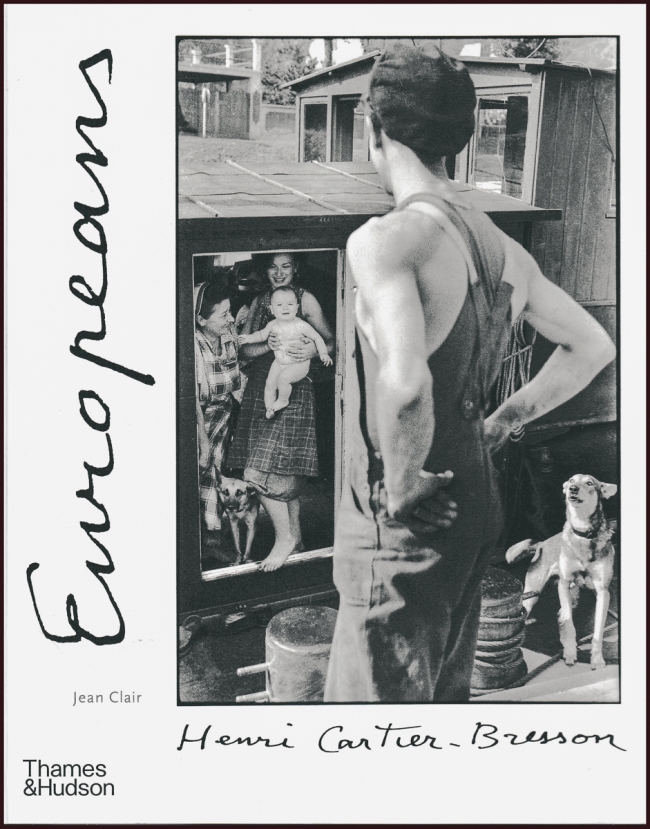

I usually post about books on or about photographers and photography. This is not one of those books. It does, however, have some wonderful historic photographs.

Doodletown was an isolated hamlet in the Town of Stony Point, Rockland County, New York, United States. Purchased by the Palisades Interstate Park Commission during the 1960s, it is now part of Bear Mountain State Park and a popular destination for hikers, birdwatchers, botanists, and local historians. It is located north of Jones Point, west of Iona Island, and southeast of Orange County. The former settlement is now a ghost town. Members of the first family to settle in Doodletown during the 18th century, Huguenots whose last name was anglicized to “June”, were also the last to leave it in the 1960s. (Wikipedia)

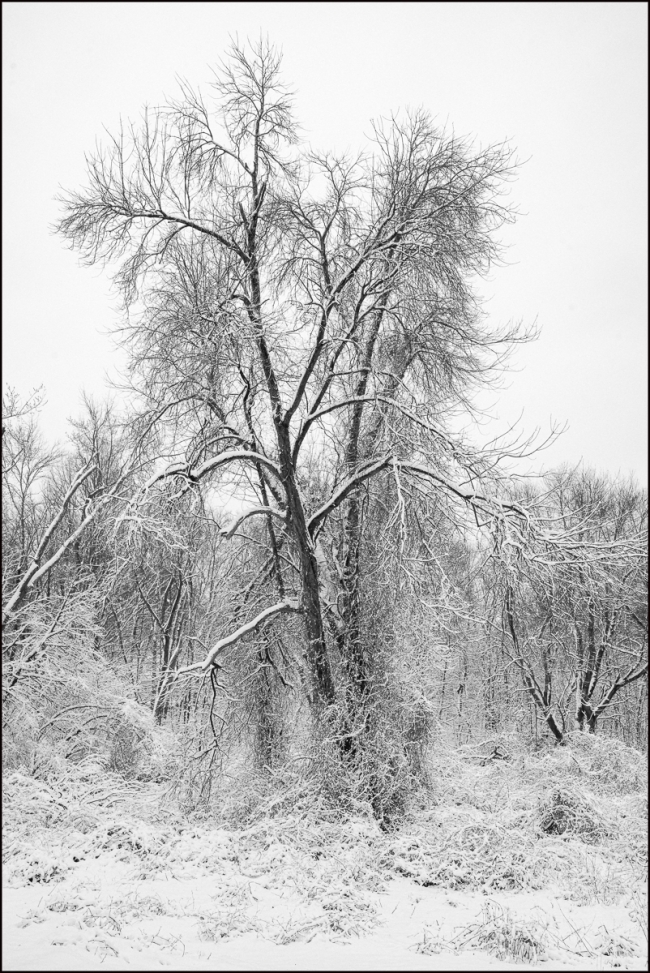

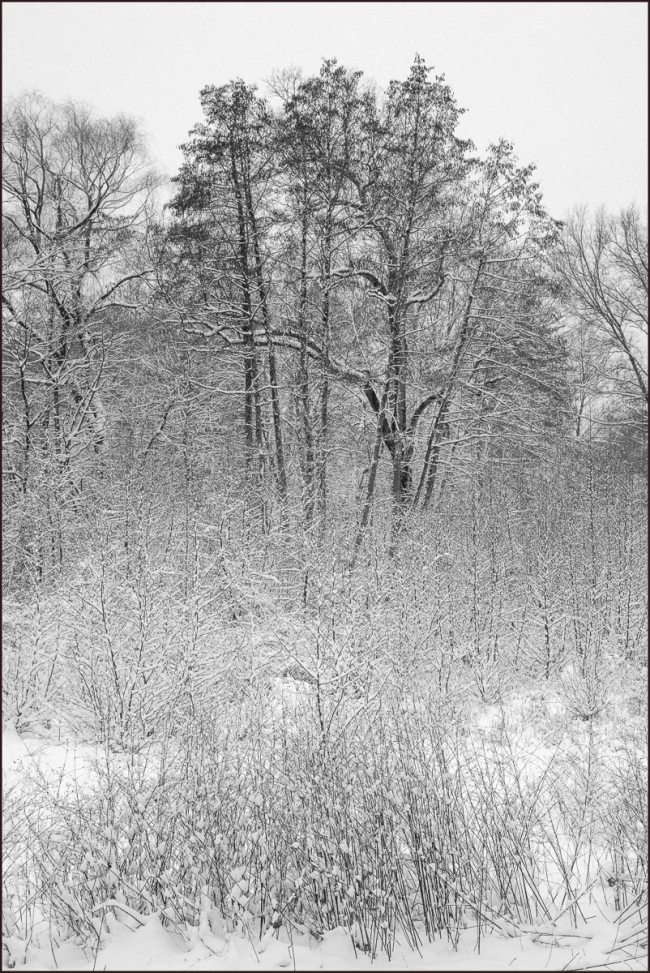

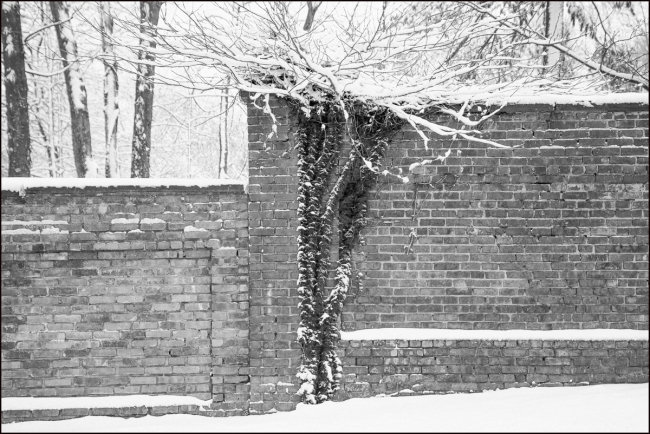

I’ve been there a couple of times and on one occasion took some pictures:

A Walk to Doodletown – Doodletown Overview

A Walk to Doodletown – The 1776 Trail

A Walk to Doodletown – Reservoir

A Walk to Doodletown – June Cemetery

A Walk to Doodletown – There’s still life in Doddletown

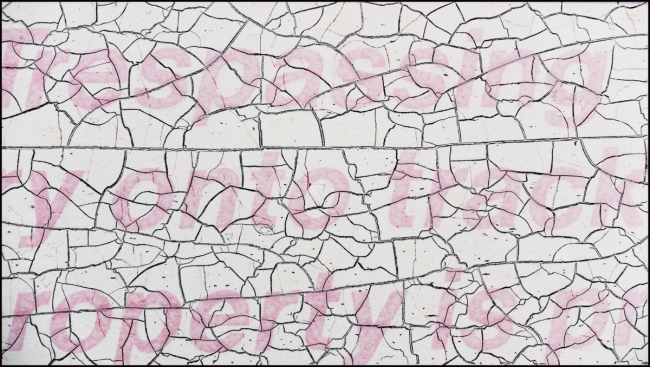

The problem with Doodletown is that there’s actually not a lot to see. Apart from a couple of cemeteries (one of them still active), mostly just the foundations of long gone buildings. At some point an attempt was made to erect information boards describing some of the former buildings, but (at least while I was there) the effects of time, weather and maybe vandalism made it difficult, and in some cases, impossible to read them. I came away wanting to know more about the history of the hamlet and its buildings.

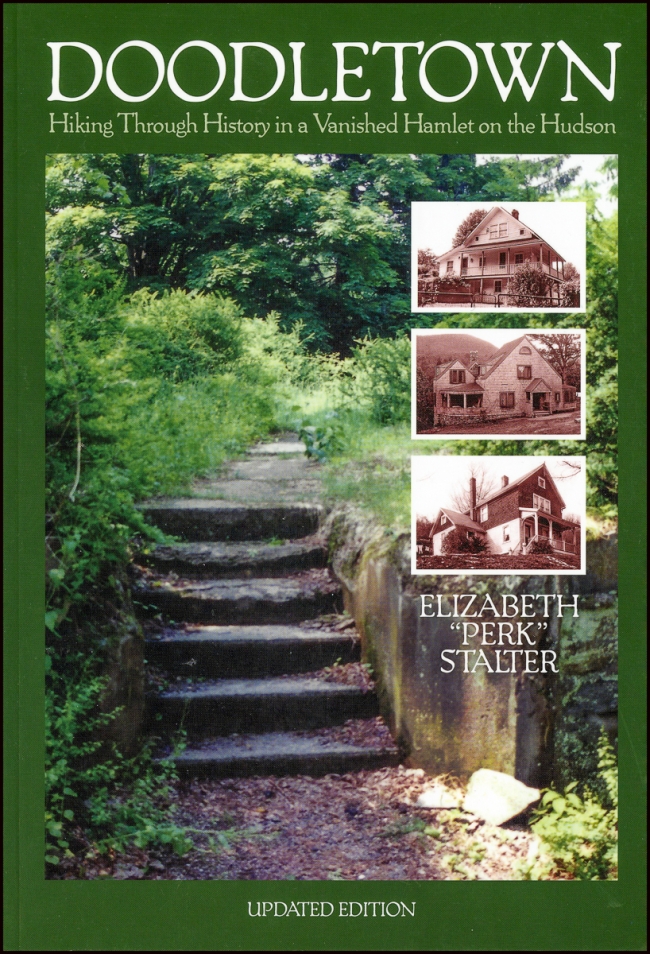

Enter Elizabeth “Perk” Stalter and her wonderful book: “Doodletown. Hiking Through History in a Vanished Hamlet on the Hudson.”

The book is divided into two parts. The first: “Did Doodletown Disappear?” largely covers the history of the hamlet from its earliest days, through the Revolutionary War period, the good times of considerable growth with new roads, new churches, new job opportunities for the inhabitants. This section also describes what it was like to live in Doodletown, describing the community and its social life; schools; shopping; law enforcement; fire protection; banking; medical services; the effects of storms and snake attacks etc. She also describes with some sadness the eventual decline of Doodletown and its assimilation into the Bear Mountain State Park. This section of the book concludes with the following:

I sincerely hope that this book will help to show your mind’s eye what our community looked like – and that it will also help you to conclude that, indeed, Doodle town did not disappear! Welcome to Doodletown!

Interesting though Part 1 was, what really attracted me to the book was Part 2: A Hiking Guide to Doodletown today. The highlight of this section are the descriptions (69 of them accompanied by photographs showing what they looked like) of all of the former buildings. This was what I had been looking for.

The book is lavishly illustrated with maps, drawings and especially photographs.

Ms. Stalter lived in Doodletown from 1950 to 1958 and her love for the community clearly comes through.

A great book. I really enjoyed. Now I’ll have to go back to Doodletown.