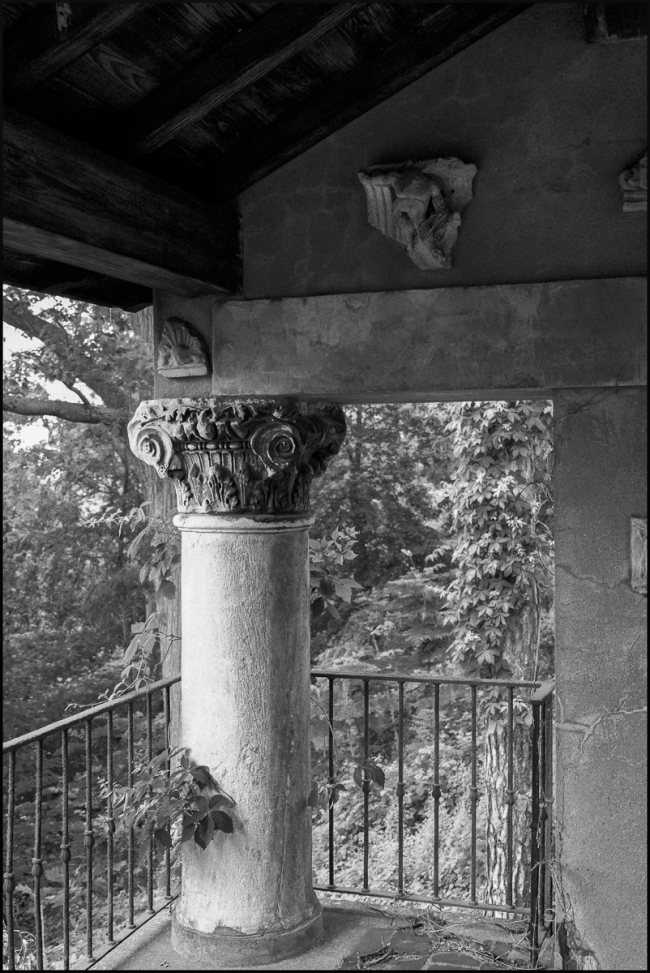

I’ve been to Untermyer a couple of times before, once in 2012 (See: Untermyr Park, Yonkers, NY) and again in 2016 (See the series of posts starting with: Untermyr Gardens Revisited – Overview). The restoration work has made great progress. When I first went quite a lot of structures were virtual ruins, now they’ve mostly been partially or fully restored. Great Work.

For years I’ve been trying to find these two statues. The first time I went I couldn’t find them because I didn’t really know where they were (they’re right at the lowest part of the property where it meets the Old Croton Aqueduct trail). Once I discovered that they were next to the trail I figured I would find them if I walked South on the trail from Tarrytown. Unfortunately my legs gave up before I got to them. I’m glad that I was finally able to get there.

Also in the picture are the deliberately only partially restored Gate House on the left and the overlook from The Vista on the right.

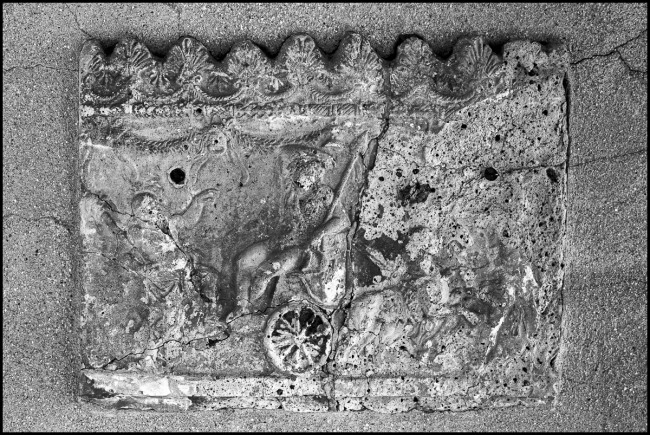

An information board nearby reads:

Opposite the gates along the Old Croton Aqueduct are a pair of monumental structures, a lion and a unicorn, symbols of the United Kingdom. From this point the mile-long carriage trail gradually climbs south up the hill past a ruined circular fountain at the lower switchback, past a meadow at the upper switchback, up to the site of the mansion, now demolished [for a glimpse of how it once looked see here. It’s a shame that it’s now gone].

.

Untermyer died in 1940. He had wished to give the gardens to the United States, to New York State or failing that, to the City of Yonkers, but because of the great cost of the upkeep of the gardens, which were not accompanied by an endowment, the bequest was initially refused by all three bodies. Finally, in 1946, 16 acres (6.5 ha) of the land was accepted as a gift by the City of Yonkers, and became a city public park. The mansion itself was eventually torn down.

Because of inadequate funding, much of the property was not maintained; a number of structures gradually fell into disrepair, and parts of the site became overgrown, reverting to woodland. In the 1970s an effort was made to restore the garden by Yonkers Mayor Angelo Martinelli, architect James Piccone and Larry Martin, but the campaign was short-lived and the property deteriorated again. In the 1990s community leaders such as Nortrud Spero and Joe Kozlowski and the Open Space Institute persuaded Mayor Terence Zaleski to purchase more of the original estate’s land with the help of the Trust for Public Land, resulting in the 43 acres (17 ha) of the park today.

Untermyer Park and Gardens was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1974. Since 2011, the Untermyer Gardens Conservancy, a non-profit organization, has been working on restoring the gardens, in partnership with the Yonkers Parks Department. Grants from New York state of $100,000 in 2005 and $65,000 in 2009 helped to finance the renovation and rehabilitation of the park.(Wikipedia).

For more information on both the gardens as a whole and these statues in particular see “A Forgotten Part of a Once Forgotten Garden” by Barbara Israel. You can see some of the progress achieved here. In the article the unicorn is lacking a head. It has since been replaced as seen in the second picture below.

I’ve recently discovered a darker side to the Untermyr property. During the period when it was virtually abandoned and not maintained it is alleged that it became a base for satanic rituals involving, among others, infamous Son of Sam killer David Berkowitz. For more information see: Ritualistic Sacrifice and the Son of Sam: Satanic Worship in America’s Greatest Forgotten Garden: by Megan Roberts on Atlas Obscura.

First picture Taken with a Taken with a Fuji X-E1 and Fuji XC 16-50mm f3.5-5.6 OSS II and the last two with a and Fuji XF 35mm f1.4 R